1 April 2015 Edition

The trouble with the euro

For Germany and its allies, a SYRIZA success would set a dangerous example to Ireland, Spain and Portugal

AS RELATIONS between Greece, under its new anti-austerity government, and the major powers of the Eurozone (particularly Germany) continue to deteriorate, the future of the troubled currency looks increasingly shaky.

The problem is that the currency was flawed – probably fatally flawed – from the start because it was a political project rather than an economic one, with the participating states being forced into a straitjacket of fiscal policy laid down by Germany.

Ireland’s membership of the euro played a major part in creating the housing bubble and the financial and economic crisis that produced. It did this because, at a time when our economy needed higher interest rates in order to dampen house prices, German policy dictated that there would be lower rates.

And when we needed lower rates, Germany needed higher ones. The fact is that our economy never got in sync with Germany for the simple reason that Britain and the US remain much more significant trading partners for us than continental Europe.

It would, of course, be politically desirable to shift that balance, but that would require the co-operation of Germany and France. However, as the 1992 devaluation of the punt showed, Germany let us sink rather than give us support, in marked contrast to its attitude to Denmark.

The current euro crises show again that Germany has no interest in giving us help and that those who believe that EU goodwill can bring about a change of attitude in terms of economic policy are sorely deluded.

The point is that the euro is part of the European project of creating a supra-state in Europe. It was implicit from the foundation of the European Economic Community (EEC) and was formally endorsed in the Maastricht Treaty (1992) which established Economic and Monetary Union.

Sinn Féin, like other parties and organisations upholding national sovereignty, campaigned vigorously against Maastricht. Events since have proven the party completely right on this issue.

Maastricht established the idea of the euro currency, which finally came into effect in 1999 as a virtual currency and 2002 as one for actual use.

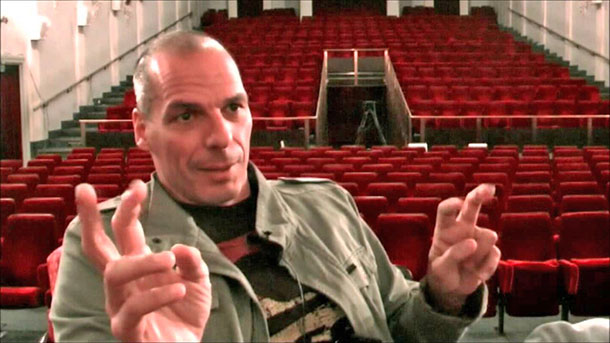

• Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis

Adopting the euro was a sign that the dominant political forces in Ireland were accepting an end to national economic sovereignty.

As mentioned earlier, since our economy was not in fact in sync with that of those who dominated the euro, the impact was disastrous for us.

The euro is now in a highly volatile and dangerous state. Over the past year it has lost 25% of its value against the US dollar. While multinational exports to the US and Britain have expanded, our trade with the Eurozone continues to stagnate.

This is the reality of the much-trumpeted economic recovery the Government is boasting about: the US and British economies are in real recovery and we have benefitted a bit from that but the Eurozone continues to drag us down as austerity ravages the economies of Europe.

Germany and its northern European allies hope that the southern states (Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain) can be isolated, thus avoiding contagious catastrophe for themselves.

That is why it is so vital for them to make sure that SYRIZA in Greece does not achieve the desired result – for a SYRIZA success would set a dangerous example to Ireland, Spain and Portugal, countries whose governments shamefully are the most adamant in demanding no concessions to the Greeks.

But SYRIZA itself has problems to confront. While tactically it is right to call on the European Union to live up to its rhetoric of common help, it would be a dangerous illusion to believe that the EU is anything other than the enemy here.

For the EU is a Rich Man’s Club (as Sinn Féin has said many times) and operates in the interest of open-market economies, by definition against the interests of smaller economies like those of Ireland or Greece.

And while disillusion with national institutions in both Ireland and Greece made an external currency like the euro superficially attractive, it is in fact a millstone around our necks unless it – and the EU – can be radically reconstructed.