12 January 2015 Edition

I Am Alone

• Walter Macken

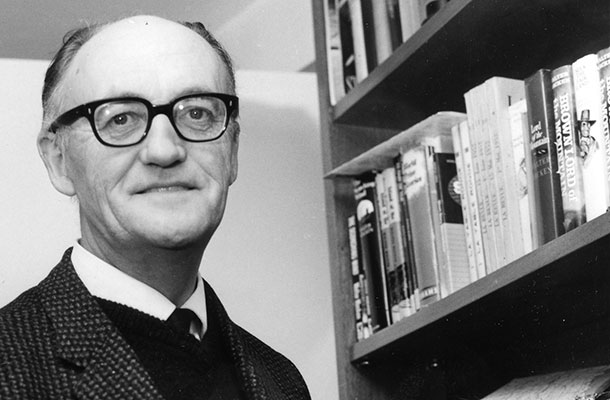

WALTER MACKEN never had time for the literati and they never had time for him, but surely the time has come for the Galwayman to be recognised as one of Ireland’s greatest writers.

When Bháitéir Uí Mhaicín died following a heart attack at the age of 51 on 22 April 1967, Irish literature lost one of its greatest talents.

And it didn’t know it.

A storyteller in the tradition of the seanchaí, Walter Macken’s stories came from the people around him in his native city and county, and in the wider province of Connacht.

They populated his novels, plays and short stories with all their contradictions, fears, hypocrisies, idiosyncrasies, prejudices, lies and secrets in full colour. Macken’s lively characters, smooth narrative flow and subtle plot weaving made his books difficult to put down but it also made his novels appear lightweight.

Never recognised as a literary giant, Macken lived an existence that eluded stereotype, not least by those who believed, in the 1960s, that Irish literature began and ended with W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett and the emerging William Trevor.

Macken appeared to be a very public figure, an actor who had starred in two films (Home is the Hero, with Eileen Crowe in 1959; and The Quare Fellow, with Patrick McGoohan in 1962); who strode the stage in Galway, Dublin and New York; who transcended his modest background to project himself as a man of many talents. But this was a mask he wore to protect the inner image.

Behind the mask was a sincere family man who had doubts about his talent as a writer because, at heart, he saw himself as no different to the people he had grown up with.

“When I die and they carry out an autopsy on me, I hope that they will see ‘I Am Alone’ engraved on my heart,” he is reported to have said. Without a context, it is impossible to know exactly what he meant. His eldest son, also Walter, a priest, thought he knew but was never sure.

“He’d get up very early in the morning and go to Mass (the only reason I’m a priest is because he went to Mass every day) and then he’d come home, smoke a cigarette, curse his lot and wish he were a train driver. We’d say, ‘Daddy, do you think being a train driver is easier?’

“He’d walk around the dining room table where his old Royal typewriter was laid, curse his lot, then he’d sit down and begin to write. Now he’d write from his head to paper, there was no rough notes or anything. All the editing was done in his head. He’d write the particular passage and then he’d call Mammy. It would be the end of the morning and he would read it to her. She was the audience.

‘Then he’d spend the afternoon walking or fishing and thinking out the next day’s work and evening reading. He would do that for a whole year and then he’d have a novel. In the middle of it he’d get a huge big depression and he’d wish that he was a train driver again and Mammy would take him out for a walk and chat him up.”

It’s hard to believe that this man, who gave a voice to the ordinary people of Connacht, suffered from a lack of confidence. After all, he had a public profile that was very real to the people of Galway in particular and the west of Ireland in general. The universal Irish Diaspora took him to their hearts because he was one of their own writing, but there was more to Walter Macken than acting and writing.

Galway roots

He was born in Galway on 3 May 1915. Ten months later, his father, a full-time carpenter and part-time actor, was killed in France. The young Macken was brought up by his widowed mother on an army pension in Galway’s tenement streets.

He attended the Presentation school, the ‘Bish’ (one of the local Patrician Brothers’ schools) and the diocesan college St Mary’s, and at a very young age began to write, eventually following his father into drama when he became a member of Taibhdhearc na Gaillime, the Irish-language theatre, on leaving school.

There he met Peggy Kenny, daughter of Tom Kenny, founder of The Connacht Tribune, and against her father’s wishes she eloped to Dublin and then London with him. They married at Fairview Church in Dublin and went to London, where he worked as an insurance seller – an experience drawn on in his second novel I Am Alone. Two years later they returned to Galway where he resumed acting, producing and writing plays in his native language while attempting to write plays and novels in English.

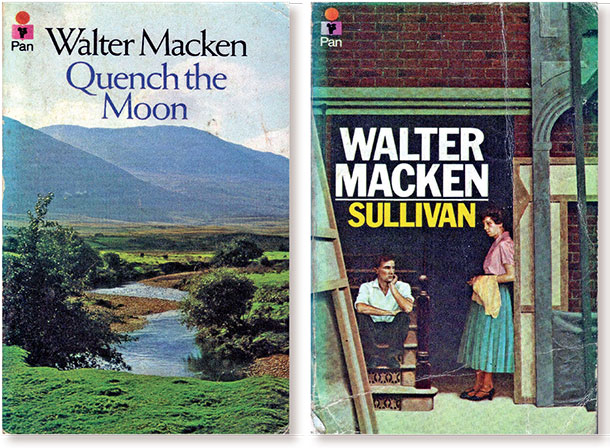

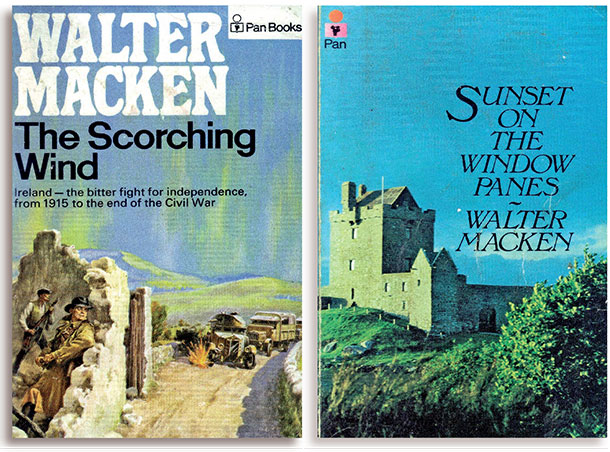

He had been at An Taibhdhearc [pronounced tiveyark] for nine years, translating the works of the great dramatists, when the news came through that Macmillan in London had accepted Quench the Moon for publication. It was his third attempt at an English-language novel. Macmillan had already published Mungo’s Mansion, his first play in English. His career as a dramatist and an actor was given a new impetus.

Walter Macken can be regarded as one of the greats of Irish literature because he wrote honestly about a period of transition in Irish society, the Celtic nationalism that Seán Ó Faoláin spoke about when he discussed the impact of Celtic paganism on the Ireland of the mid 20th century.

“If the Celtic tradition has given us anything . . . it has given that old atavistic individualism which tends to make all Irishmen inclined to respect no laws and though this may be socially deplorable it is humanly admirable, and makes life more tolerable and charitable and easy-going and entertaining.”

Banned in Ireland

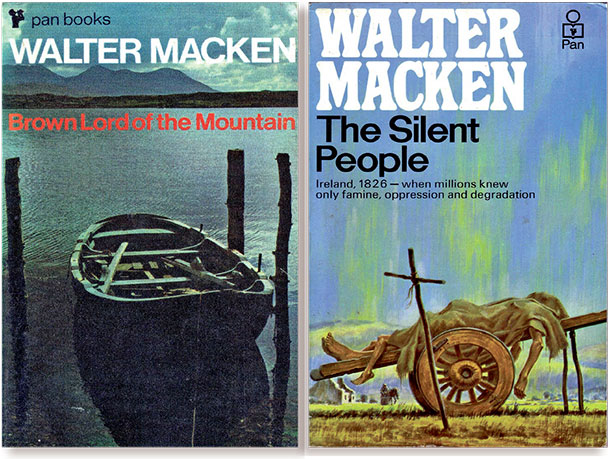

Written around the time that I Am Alone and Rain in the Wind were banned in Ireland, these words might easily transfer to a general description of the male characters in Macken’s novels. Stephen O’Riordan in Quench the Moon, Mico in Rain on the Wind, Cahal Kinsella in The Bogman, Bart O’Breen in Sunset on the Window Panes and Donn Donnshleibhe in Brown Lord of the Mountain.

Each different, everyone of them carrying a cross (another reccurring theme of Macken’s fiction), each atypical to their neighbours and surroundings, Macken used these characters to tell stories that contained morals, which allowed readers not to judge but to sympathise, for his fiction mostly depicted the marriage between idealism and pragmatism. This is seen in all his novels, particularly I Am Alone, but also in his last, posthumously-published, novel, Brown Lord of the Mountain.

Not only did Macken know and write about the people he lived among, he understood how they functioned in their daily rites of passage, and this allowed him to write characters that were as real as the day was long. It was an authentic style no other Irish writer has been able to recapture about the people of rural Ireland.

More than anything he understood that people generally helped rather than harmed each other.

Fr Macken realised this was another theme of his father’s books when he reread Flight of the Doves after it had been adapted for the screen. In the novel, two children escape their stepfather with a crazy unplanned flight of fancy to find their granny somewhere in Connemara. At every step of the way, when they explained their quest, people helped them, but when Fr Macken watched the film he realised the producers had missed the whole point of the story.

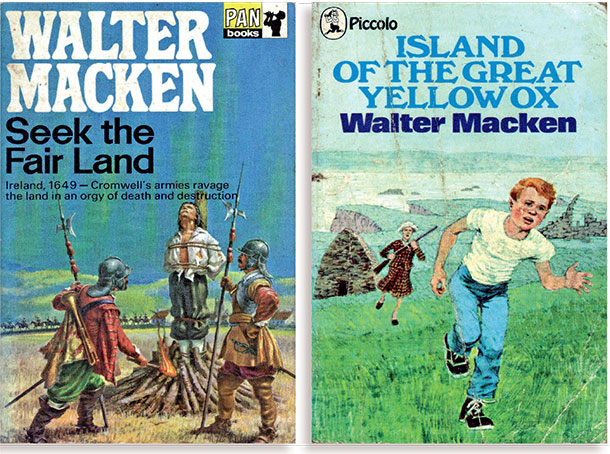

What Fr Macken discovered was another theme central to his father’s fiction. It connected Flight of the Doves with his father’s other children’s novel, Island of the Great Yellow Ox, where the children go in search of the golden ox, and he realised too his serious work, especially the first novel in Macken’s historical trilogy, Seek The Fair Land (set in the time of the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland in 1649).

“Cripes,” Fr Macken thought. “What an image. Wow! The whole image of Seek the Fair Land is a man looking for peace somewhere or other and can’t find it in Cromwell’s bloody Drogheda so he heads for the west. He doesn’t find it there either but he finds it in his heart. That work went through a lot of the books.”

If this is the philosophical element running through the ideological core of Macken’s fiction, the pragmatic aspect of everyday life is there at the edges. Aengus Ó Snodaigh, reviewing the re-released Brandon editions of Sunset on the Window Panes and The Bogman, summed up Macken’s ability to see under the skin of the people, to understand their everyday fears and feelings, to reveal “the little secrets of life, which are hidden away by the people or the community for fear of upsetting the equilibrium of their way of life”. This wasn’t romantic at all, it was instead tough life, how the destructiveness of secrets impacted on communities and individuals.

Secrets played a huge part in Macken’s fiction because they were woven into the fabric of the rural life around him, but if Brinsley McNamara’s The Valley of the Squinting Windows is a tragedy in a literary context and as a moral on Irish society, only Macken’s Brown Lord of the Mountain can be seen similarly.

Macken should have been acknowledged by his literary peers, and if Knut Hamsun was worthy of Nobel’s literary prize for The Growth of the Soil with his depiction of Nordland life, the Galwayman’s body of work about the west of Ireland was equally meritorious.

Unfortunately for Macken, those who read and appreciated his work weren’t in the habit of writing letters or hanging out with the literati. The Establishment, as it had always done, ignored his work.

Walter Macken, his eldest son realises, was tormented by the ghosts of his country’s and his own past and present, phantoms that would challenge his ability as a writer.

“There were times when Mammy would have to persuade him two, three, four times a year that he was a good writer. ‘Don’t worry,’ she’d say, ‘of course we’ll survive.’ He would always worry about money. My father was a peasant. In his blood he was a peasant, you see.”

From this perspective, Macken wrote his stories using a narrative style that was visual, portraying the minute details of the ordinary people of Ireland.

“The little man is important to Walter Macken,” Fr Macken told audiences who came to hear some wisdom about his father. “All his books from the very beginning are full of the little man. They are about everyday people and their everyday battles, their joys and their sorrows, their lives and their deaths, because this is reality for the world of Walter Macken.”

• The Quare Fellow, with Patrick McGoohan, 1962