12 January 2015 Edition

Owning the pain we have caused

UNCOMFORTABLE CONVERSATIONS

• Earl Storey in Rwanda

To be involved in reconciliation means to be willing to take ownership of pain. That is where the really difficult and painful conversation is

SOMETIMES it is because churches are places of such beauty or history that silence is the only appropriate response. Sometimes – but not always.

Nyarubue Church is no ordinary place. Not now. Set in a village high in the hills of eastern Rwanda, it was a place that thousands of people fled to in 1994. As a church, surely it would provide a place of sanctuary for people fleeing genocide? In a country and at a time when neighbour was turning against neighbour it seemed to offer one of the few places of safety and security. Such was not to be the case.

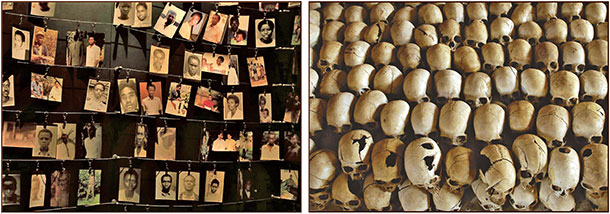

Over a short space of time the church and its environs became thronged with terrified people. It was at such a time that someone gave the word to the militias. What followed was an attack on the church in which over 25,000 people were murdered. What was meant to be a sanctuary became a mass killing ground. Some of those who ought to have been protectors had in fact been the betrayers.

• Nyarubue Church became a killing ground

It is a brutal fact that during the 1994 genocide in Rwanda the machete was most often the weapon of choice. In the space of one hundred days, approximately one million people were murdered in this country. Perpetrators did not come from afar. Murder, rape and maiming were committed by fellow citizens. It was quite literally a case of neighbour against neighbour. On occasion it was even family member against family member. What prompts the citizens of a country of approximately eight million people to such acts of intense madness?

It was in 2004 that I visited Rwanda. It is always easier to preach a difficult message of reconciliation to someone else in a far away place. On my first Sunday I was guest preacher at a local parish. My sermon was on the story of The Good Samaritan. Jesus was explicit about what was needed to inherit eternal life – to love God more than anything else, and to love our neighbour as ourselves. For the Good Samaritan, loving his neighbour meant tending to the needs of his Jewish enemy.

Later I discovered that in the church were those orphaned and widowed by the genocide. Also there were people who by action or silence had committed such terrible acts. Both sides of the conflict were part of that congregation. To talk about loving your neighbour as yourself, in the terms of the Good Samaritan, was not lost on these people. How far that country has travelled in such a short time towards reconciliation – one of the poorest countries in the world.

• One million people were murdered during the Rwandan genocide

I once asked an overseas Catholic monk what he saw when he looked at our country. His answer was immediate and to the point: “What I see is a deeply-wounded community.”

The wounds are the wounds of violence. During the years of ‘The Troubles’ I took part in a number of funerals of people killed and visited bereaved families. My overwhelming thought each time was: “If only those who caused this could be here to see the consequences of what they have done, to witness the raw pain from such a terrible wound inflicted on a family.” It was not about revenge but about appreciating the cost of violence on another human being.

More recently I was really taken by surprise listening to a neutral foreign visitor address a gathering. When asked to reflect on the state of the Peace Process, the visitor said in a very definite tone, “One of the things you have to come to terms with here is . . . guilt.”

To be involved in reconciliation means to be willing to take ownership of pain. That is where the really difficult and painful conversation is.

In Rwanda, there seems to be an agreed narrative about the awfulness of what happened in 1994. No one tries to justify or excuse what happened. There is no appetite for calling it something other than what it was. This honesty is a vital part of what makes reconciliation possible. This seems to be absent here. Yet airbrushing the past will impede rather than enable reconciliation.

What is this Peace Process about? Is it about breaking a historic cycle of division, hatred and violence? Or is it to be little more than a breathing space until the next round of fighting? The decision depends on having that most uncomfortable of conversations – where we own not only our own pain but also that which we have caused.

So does the Republican Movement want to be a reconciler? It talks much about armed struggle. Armed struggle is by neighbour and against neighbour. By its very nature it is deeply wounding. Facing and ‘owning’ the wounds caused is the start of a conversation. Anything else is just talk.

“Reconciliation is the only way to live together. The only way to finish our conflict” – Archdeacon John Marara (Rwanda)

• Reverend Earl Storey is Director of ‘Hard Gospel’, a Church of Ireland project to help in building reconciliation throughout communities troubled with sectarianism.