4 August 2014 Edition

Globalisation on the highway of life

• Global brands, chains and franchises are dominating our main streets

• • • • • • • •

A middle-aged man dressed in shirt, tie and trousers is sleeping on a couch in a spartan office. The sound of a train passing his window wakes him.

“I had a nightmare,” the man says, sitting up. “I dreamt that the bombers were coming.”

A woman is sitting on a park bench, talking to a man sitting beside her, holding the reins of a dog.

“A motorcycle is my dream,” she starts to sing, after telling him and the dog to get lost. “I’d be so happy that I’d scream.

“Lovely thing with blazing speed, to leave this place is what I need.

“It takes a pile of dough, and a licence, you know.

“But I’m all out.

“And that I’m pretty pissed and mad about.”

A worker sitting in a truck in traffic explains the contents of a dream.

In the dream he tries and fails to pull off the old tablecloth trick, dragging an antique dinner-set crashing to the floor. The police are called, he is taken to court and told he is guilty of “gross negligence and destruction of property”.

Three judges offer sentence.

“Life sentence,” one says.

“Not enough,” says another.

“The electric chair,” says the third.

They and the jury agree. “The electric chair, going once, twice, three times.”

One of the judges bangs his gavel. “The electric chair!”

“That’s life,” the dream-worker tells his sobbing defence counsel.

Back in his truck the real-time worker comments: “The electric chair. What a terrible invention. How could you come up with such a thing?”

In a restaurant, a businessman takes a call on his mobile. “We are sitting here celebrating, and the gods are congratulating us with thunderous applause,” he laughs to the sound of thunder.

“No money, no tournedos and no Bordeaux either,” he retorts in response to the caller, who appears to be the fixer in a deal. “That’s brilliant, Toby. You are a goddamn poet.”

Meanwhile, a man in the table behind removes a wallet from the businessman’s jacket pocket on the back of his chair, then pays for his own lunch with cash from the businessman’s wallet, and leaves.

“Quality is not for the common man. Never has been, never will be,” the businessman says ambivalently. “How did that philosopher put it? You can’t play nice in war and business. Or something like that.”

Then he notices his wallet is missing.

The wallet thief goes to a tailor’s to be measured for a quality suit.

An ageing psychiatrist tells his assistant he is worn out. “People demand so much,” he says.

“That’s the conclusion I’ve drawn after all these years. They demand to be happy at the same time as they are egocentric, selfish and ungenerous. Well I would like to say they are mostly mean.”

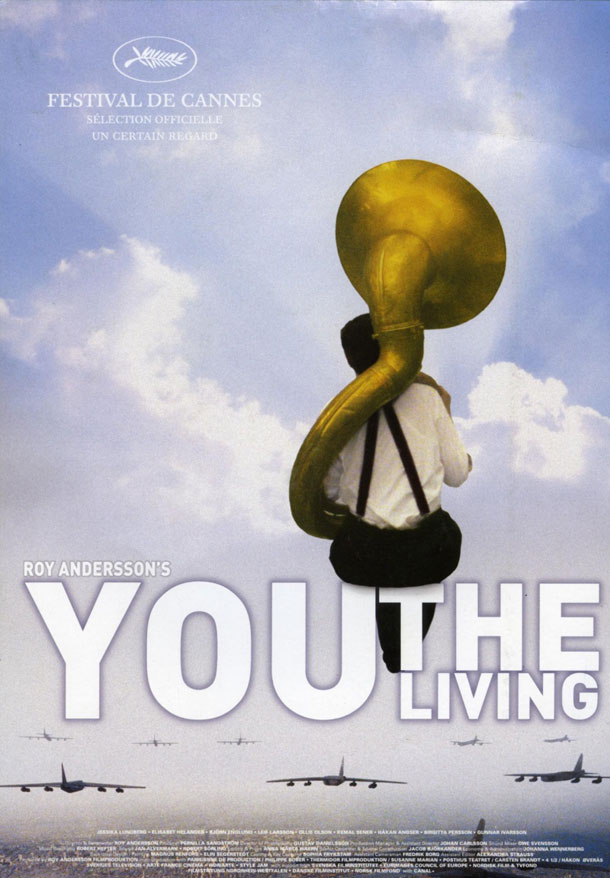

These are some of the opening sequences in Swedish film-maker Roy Andersson’s You, the Living.

A shot showing commuters disembark a tram in the morning gloom is a clue to this tragicomical content.

Its destination is Lethe!

• • • • • • • •

ROY ANDERSSON made his reputation with brilliant TV commercials. He employs fixed wide camera shots in his feature films. Static perspectives are often revealing, especially when all the action appears to happen within the immediate viewpoint.

To understand Andersson's work the viewer must pay attention to the background as well and not just watch the action and listen to the dialogue in the foreground.

The same might be said about globalisation and its impact. Nearly everything that has been said and written about it also comes from a fixed perspective – from academics, activists, commentators, economists, journalists and politicians.

But every one of them misses the big picture. They even miss the detail. And they certainly do not see the irony.

That is largely because the majority of these people are not affected by globalisation. In fact, most benefit or are immune from it.

They do not see what is going on in the background.

How could they? It is not possible to live the lives of others, and why would you want to!

“We all need respect, attention and love,” says Andersson ruefully.

Globalisation has been gradually removing these powerful emotions from our lives and selling them back to us as commodities we cannot afford.

A GENERATION has grown up since Edward Abbey lambasted the hidden persuaders who changed our world a generation earlier, in the 1960s when television was a flickering monochrome screen.

By the time colour TV arrived, the men of Madison Avenue had constructed the rules of globalisation, and devised the methods that have made us buy into the American Dream.

In Ireland, in less than 45 years, local business activity has decreased by two-thirds while global business activity has increased by nine-tenths.

Global brands, chains and franchises dominate our main streets largely to the detriment of indigenous artisans and entrepreneurs, who are told to export and grow . . . or die.

Many local businesses struggle to survive because they are competing with global businesses who can undercut prices and control supply.

When the majority of the population cannot afford to pay higher prices it is local businesses that suffer and global businesses that benefit.

Modern Ireland became a well-oiled machine designed to promote globalisation in the late 1960s. It eventually produced a boom-bust cycle, as capitalism had a habit of doing throughout the 20th century. Now it is business as usual again. The dominant paradigm is globalisation at all costs!

THERE IS NOTHING inherently wrong with the idea of globalisation, especially if employment and opportunity are the consequences. But globalisation is not about providing well-paid jobs and generating local-global initiatives.

It is about elitism, selfishness and the insane pursuit of profits and wealth through the exploitation of labour, resources, trade and the universal market.

The people who control the means and methods of production and supply are egotisical by their nature. They want to live in big houses, eat in fancy restaurants, revel in their splendour and escape the humdrum of life several times a year at exotic locations.

Kerry Bolton, author of Babel Inc, argues that everyone has a desire to follow this yellow brick road to prosperity, blissfully unaware that only a lucky few get to dance with the global oligarchy.

And Bolton believes the “rank and file” of activists – especially Left-oriented anti-globalisation campaigners – are “clueless” about the elements of globalisation.

WHEN the American eco-anarchist Murray Bookchin first postulated his ideas about a new ecological society based on a process of collective, non-hierarchical autonomy, he did not imagine the idea would be so difficult for people to grasp.

He failed to notice that most people usually only respond to single-issue campaigns, when their livelihoods, health and safety, environment and way of life are threatened. Like many of his kind he assumed that altruism rather than careerism was the sole motive of the political activist and the ecological entrepreneur.

“The term anti-globalisation is a mistake, as most of us are pro-globalisation,” argues Tim Barton, editor of BlueGreenEarth, a social-ecology magazine. “It is corporate neo-liberal globalism we seek to destroy.”

The problem, as Bookchin learned too late, lay in the old Left ideologies, negative globalism based on the top-down imposition of collectivism.

This permeated the anti-globalisation movement at the same time the lifestyle activists came to prominence. It was one thing to want to change the world without taking power, another to want to opt for alternative lifestyles and yet another to want to have choices and opportunities (and pursue practical dreams).

Show-and-tell has never been part of anti-global activism and organising, much to Barton’s annoyance.

“The biggest threat to neo-liberal capitalism comes from opposition that is self-aware and that is able to see the importance of acting locally and thinking globally.

“The state’s greatest ire is reserved for those that achieve this. Ironically, the most media friendly and high-profile of these ‘anarchists’ are usually middle-class lifestyle activists, on sabbatical from their careers in the capitalist system.

“The middle-class enclaves of apolitical NGOs, who are highly prominent actors in civil society, often marginalise and suffocate popular initiatives, as they often seek to competitively control and dominate debate and are prone to taking decisions determined by their funding requirements.

“The bottom line is that the populations of the democracies of the developed world do what they are told, are engaged in specialist careers that enhance profits, and collapse into deskilled, panic-stricken mobs when economies fail.”

PRO-GLOBALISERS like Philippe Legrain (who believes elected governments are still in control), Alan Shipman (who believes big corporations are the true rebels against conservatism), and Joseph Stiglitz (who believes the opponents of globalisation are deluded), seem to be suggesting that the debate is over.

Almost five years ago, Belfast-born human rights academic David Kinley made a valiant argument about globalisation.

“The provision of economic aid, the expansion of global trade, and the establishment and development of commercially robust economics are, or can be, mechanisms for stimulating chain reactions that increase individual and aggregate wealth, alleviate poverty, promote opportunities and freedoms, and strengthen governance.”

Since he wrote these words in Civilising Globalisation: Human Rights and the Global Economy, the economies of many countries have been anything but robust.

Sadly, those who see the impact of globalisation on daily life are not prone to philosophy, and being outside society are unable, despite social media, to have their voices heard.

They argue that new approaches with different values must be made.

They dismiss the old radical ways – disapproval via political movements and dissent via social movements and trade unions (which always result in alliances that disempower and institutionalise) – because they have been shown to be redundant and useless.

They argue for human-scale initiatives suited to the modern world: decentralisation; ecological awareness; egalitarianism; ethical, moral and harmonious interactions; face-to-face civic management; local systems of production and distribution; mutual aid; resistance to hierarchy and dominance; and sustainability.

The alternative, as Andersson seems to be saying in You, the Living, is the testosterone-drenched conflict of the past.

The psychiatrist in Andersson”s film says there is no point trying to make people happy. “These days, I just prescribe pills; the stronger the better. That’s the way it is!”

Without asking people whether they really want a world of masters and slaves, the elites are saying: ‘Live with it, that’s the way it is.’

Goethe knew what he was doing when he stated the obvious.

“Be pleased then, you, the living

“In your delightfully warmed bed

“Before Lethe’s ice-cold wave

“Will lick your escaping foot.”

At the end of You, the Living, the bombers soar overhead. The nightmare is frighteningly real, the dreams diabolically surreal.