4 August 2014 Edition

Ireland and the war of empires, 1914

Remembering the Past

Officers of unionist sympathies were inclined to see in a British continental intervention one possible means of postponing or preventing altogether the introduction of Home Rule – Historian Christopher Clark

AS we mark the centenary of the start of the First World War, MÍCHEÁL Mac DONNCHA looks at how that imperialist conflagration commenced and Ireland’s role in it.

AS THE LITTLE YACHTS Asgard and Kelpie sailed for Ireland with arms for the Irish Volunteers in mid-July 1914, a massive European political and diplomatic crisis was escalating. Before the end of that month it resulted in a war that engulfed Europe and much of the wider world, lasted over four years and took millions of lives.

The immediate cause of the crisis came on 28 June with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo. Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the assassin was a Bosnian-Serb nationalist, a member of a group of conspirators secretly backed by the military forces of the independent state of Serbia. The movement for a ‘Greater Serbia’, including territories within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was seen by that empire as a real threat.

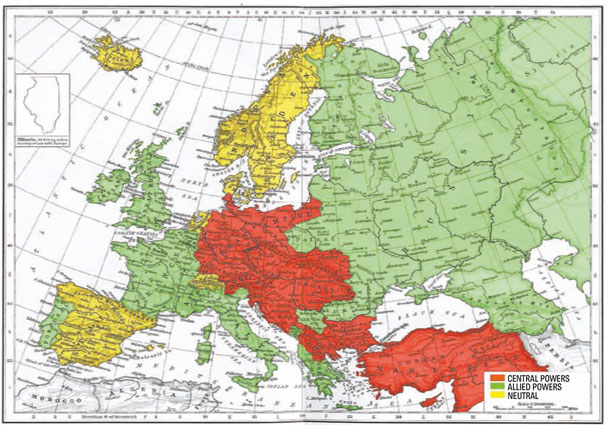

This regional confrontation in the Balkans was turned into a continental and global conflict by the competing interests of the great European empires – Austria-Hungary and Germany on one side; France, Britain and Russia on the other. All were ruled by privileged elites and in each empire the power of the military and of the capitalist owners of industry (including the arms industry) far outweighed any restraint that the people could exercise on their rulers.

Even in Britain, regarded by some as the oldest and most stable parliamentary democracy, foreign policy was not subject to real Cabinet, let alone parliamentary, control. British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey conducted this policy himself, sharing little information with the Cabinet as the crisis developed.

An indication of the power of the military and of Ireland’s place in British imperial policy has been highlighted by a recent, much-praised study of the origins of the war (The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, by Christopher Clark, Penguin 2013).

In a memorandum for the British Cabinet on 29 June 1914, the day after Sarajevo, the British Army’s Director of Military Operations, Henry Wilson, a staunch supporter of Ulster unionism and opponent of Home Rule, argued that the army would need to deploy the entire British Expeditionary Force to Ireland if it were to impose Home Rule and restore order.

This would mean renouncing any military intervention in Europe for the foreseeable future. But a military intervention in Europe would mean the postponement of Home Rule – and that is precisely what happened. As Clark states:

“This meant in turn that officers of unionist sympathies – which were extremely widespread in an officer corps dominated by Protestant Anglo-Irish families – were inclined to see in a British continental intervention one possible means of postponing or preventing altogether the introduction of Home Rule.

“Nowhere else in Europe, with the possible exception of Austria-Hungary, did domestic conditions exert such direct pressure on the political outlook of the most senior military commanders.”

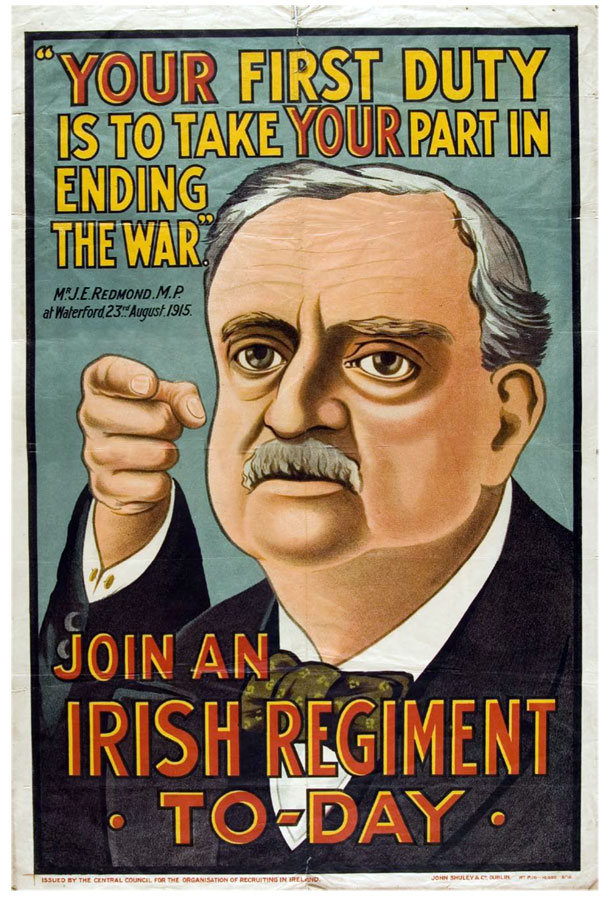

• Irish Party leader John Redmond on a British Army recruiting campaign poster

The anti-Home Rule mutiny of British officers at the Curragh in March 1914 (which had the approval of Henry Wilson) showed where the British Army stood. This was underlined again on 26 July 1914 when the British Army shot dead three civilians on the streets of Dublin after the ‘Howth Gun-Running’. Two days later, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and the Czar of Russia ordered the mobilisation of his massive army.

It was then that the system of alliances kicked in and the British Government was faced with the question of intervention – and Ireland would have to respond to the British decision.

The British had grown increasingly wary of and hostile to the growing industrial and military power of Germany. The British jealously guarded the supremacy over maritime commerce that the powerful Royal Navy gave them. British foreign policy became concerned with cornering Germany and thus the British had allied with their previously deadly enemies, France and Russia. The latter alliance in particular was controversial in Britain where much Liberal opinion deplored the tyrannical Czarist regime.

The war began nominally between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, with Russia joining on Serbia’s side. But the Russian mobilisation sparked fear in Germany that Russia and France would crush her between them. Thus German war plans, prepared years before, had envisaged a speedy invasion of France, knocking that country quickly out of the war before Germany turned east to go on the offensive against Russia.

Up to 3 August, when Germany declared war on France, the British Government had yet to intervene. The next day, Britain declared war on Germany.

The war party in the British Liberal Government and the military commanders had long prepared for this but there was still opposition to war among a section of the Liberal Cabinet as well as in Parliament and in the country generally.

The German invasion of Luxembourg and violation of Belgian neutrality was skilfully used to crush anti-war sentiment. It was conveniently overlooked that Britain was now in a military alliance with Russian Czarism which suppressed many nations, and that Britain herself, like France and Belgium, was an imperialist power denying the independence and self-determination of nations across the globe.

One of those nations was, of course, Ireland.

It was only among republicans and socialists in Ireland that there was a clear view of where the country should stand with regard to the war.

As far back as Wolfe Tone, republicans had realised that true independence for the Irish people included the right to decide their own foreign policy. This was reflected in the politics of the Irish Republican Brotherhood which, in 1914, was preoccupied with building up the newly-formed Irish Volunteers.

When war broke out, the IRB had just fought an internal battle for control of the Volunteers. Reluctantly, the IRB had to accept onto the Provisional Committee of the Volunteers the nominees of the Irish Party leader John Redmond.

He and his allies had long accepted Home Rule (yet to be implemented, though passed in legislation) as a final settlement with Britain. Home Rule, of course, allowed for no foreign policy role at all for an Irish government.

And Redmond had already conceded to the British Government the principle of partitioning Ireland.

At the start of the July 1914 crisis, the main issue before the British Cabinet was not the danger of war in Europe but the partition plan. Redmond had come under severe criticism from republicans for his participation in what James Connolly called “dismembering Ireland”.

It was no surprise then that when war came the Redmondites within the Irish Volunteers took Britain’s side. The divisions between them and the republicans were reflected, albeit in a muted way, in the pages of the Irish Volunteer newspaper, in which both sides wrote.

The 8 August issue reported the outbreak of the war. Its sheer scale was understood right away with the front page declaring that “history has no record of such a widespread conflagration”.

Its importance for Ireland was also understood.

“Tone in his brightest dreams never imagined a more glorious opportunity for the land he loved than now opens for Ireland if her sons are only loyal enough and brave enough,” declared the paper. It speculated that British troops would be withdrawn and the Volunteers left to defend Ireland.

But in the House of Commons on 3 August, Redmond had pledged to defend Ireland – for Britain – using the Irish Volunteers. This is reflected in the paper’s commentary on 15 August with the claim that “Ireland’s interests and England’s interests in this conflict run together for a considerable distance”.

There is a sharp contrast between the editorial line in the paper of 22 August and the issue of the previous week, reflecting deep divisions behind the scenes between the Redmondites and the republicans. “Conquest by England or France is as damnable as by Germany or any other foreign power,” declares the front page.

Redmond was at this time actually talking to the British about them arming the Volunteers to defend Ireland –– as part of the British Army. Discontent among many Volunteers at the rumours of their being taken over as part of the British Army is reflected in a letter to the paper from W.K. McDonald and headed “Ireland not the Empire”.

In a letter to Joe McGarrity in Philadelphia on 12 August, Pádraig Pearse wrote:

“Publicly, the [Irish Volunteers] movement has been committed to loyal support of England; not officially so far but by implication. To everyone in Ireland that has any brains it seems either madness or treachery on Redmond’s part . . . The British Government will arm and train us if we come under the War Office and accept the Commander-in-Chief in Ireland as our generalissimo.”

Pearse correctly predicted that if Redmond directed them to submit to this the Irish Volunteers would split, as they did in September.

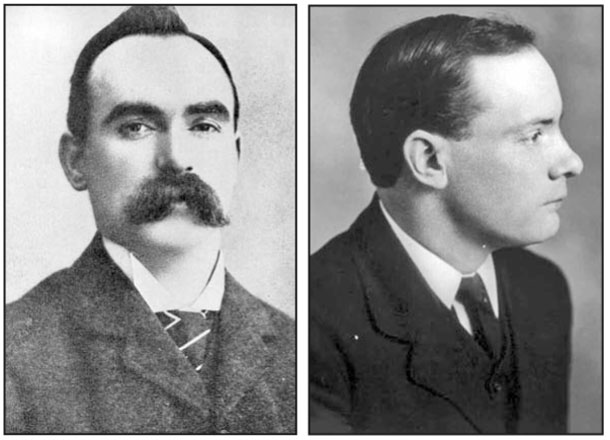

• James Connolly and Pádraig Pearse

On 8 August, in the Irish Worker newspaper, James Connolly gave the clearest and strongest view of what Ireland’s attitude to the war should be:

“Should a German army land in Ireland tomorrow we should be perfectly justified in joining it if by doing so we could rid this country once and for all from its connection with the brigand empire that drags us unwillingly into this war.

“Should the working class of Europe, rather than slaughter each other for the benefit of kings and financiers, proceed tomorrow to erect barricades all over Europe, to break up bridges and destroy the transport service that war might be abolished, we should be perfectly justified in following such a glorious example and contributing our aid to the final dethronement of the vulture classes that rule and rob the world . . .

“Starting thus, Ireland may yet set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last warlord.”