1 July 2014 Edition

Where’s the Food Harvest? Going, going . . .

Robert Allen on the road with the wandering minstrels who are Ireland’s food artisans

• Artisan Food Harvest: Raw milk vegetarian cheeses from Cavan; buffalo mozzarella, farmhouse cheese, orange jelly and red onion relish from Cork; whiskey cheese from Limerick; spelt flour from Louth; spelt bread from Mayo; mushrooms from Monaghan; smoked

Irish people in general are not being educated to appreciate food of quality

THE STONE COTTAGE shrouded in greenery at the end of the lonely boreen is picture postcard perfect. Raindrops fall reluctantly from the trees, caught by the rays of sunlight that suddenly appear in the aftermath of another thunder shower. Emerging out of a grassy wall, a woman weeding the verge indicates the modern building behind a white van. “Silke is in there,” she says in a guttral accent.

There is nothing incongruous about this setting in rural Cavan, a few kilometres from the border with Fermanagh. Artisan Ireland requires the EU stamp of approval and, just to prove this point, cheese-maker Silke Cropp explains that an inspector from “the department” is arriving to take away some cheeses for testing.

During the blistering hot summer of 1995, the Sheridan brothers, Kevin and Seamus, sold Irish cheeses in Galway’s St Nicholas Market on Churchyard Street, not expecting their little venture to last. Two years later, they moved off the street into an adjacent shop.

“There were all these fantastic cheese-makers who had invented their own cheeses,” says Kevin Sheridan, “and we were thinking, are we at a peak, as these people retire are we going to be left with none?”

• Cheese sellers Chelsea and Darryl in Sheridan’s shop, Pottlereagh, Kells

Now, almost 20 years later, Sheridans Cheesemongers operate in Dublin, Galway, Meath and Waterford, and distribute abroad. Far from the nascent industry dying, it came alive. Quality was the key; and the fact that it was hand-made.

In the 1950s, artisan production in Europe was back in the ascendancy, and cheese, followed by sausages and salamis, breads and pastries, jams and sauces, led the way.

When the Sheridans were selling cheese in the late 1990s, a third wave of Irish cheese-makers were beginning to make reputations for themselves. The second wave, cheese-lovers like Silke Cropp, were established and getting rave reviews. The first wave, in the 1970s, were already cheese legends but times were changing.

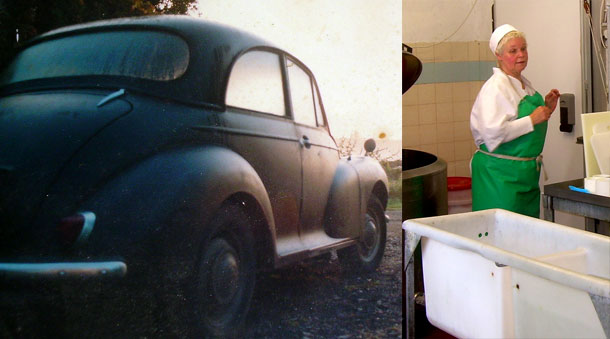

“The road to market was the biggest problem,” Silke Cropp says of the days when transport was painstakingly slow and couriers were city-based. “I thought about exporting to Germany but that was too expensive. It only started to work when I joined the Food Co-op in Dublin in 1989 and travelled in our old Morris Minor, getting up at four in the morning. It was a long day.”

• Cheese car: Silke Cropp drove to Dublin every Saturday in the 1980s to sell cheese at the Food Co-op on Pearse Street

Her children got involved, daughter Tina setting up her own stall in the new Temple Bar Market in Dublin when she was 15. They sold cow’s, goat’s and sheep’s mature cheeses made with raw milk and vegetarian rennet. At the Food Co-op their cheese appealed to vegetarians who shunned animal rennet made cheese.

“I felt that I needed direct customers if I wanted to make any money at all and that hasn’t changed. We sell to restaurants and shops and still attend the markets. My son Tom goes to Bray and I go to Dublin.”

Ireland’s food artisans are like wandering minstrels, all members of a like-minded troupe without protection to keep the wolves from the door. The wolves in this instance being high-running costs, time-consuming bureaucracy, inadequate or costly markets, and no funds for marketing strategies and promotional devices.

Yet the Department of Agriculture, Bord Bia and Teagasc love the idea of artisan producers so much they have included them in Food Harvest 2020, a ‘smart, green’ programme designed to take Irish food out into the big world and secure jobs.

Bord Bia has been given the task to secure more shelf space for artisan and small producers while the good bureaucrats in Dublin insist that “small producers are benefiting from local sourcing policies from the major supermarkets and convenience groups”.

The key to this “valuable transition from market and independent sales into multiple retail” is the capability of small companies to grow and expand into larger companies.

For Silke Cropp the idea of running a small factory defeats the object of artisan production (that and the cost of expansion, not easy when cash flow is paramount).

“We tried to sell to SuperValu in Cavan, Clones and Ballinamore; their paying policy of 90 days doesn’t work for us.”

Neither does the Artisan Food Market at Bloom run by Bord Bia. It might provide a platform for marketing, promotion and sales and reach over 110,000 consumers but it requires a cash outlay the Cropps cannot afford.

• The Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine’s Food Harvest 2020 initiative

The authors of Food Harvest 2020 appear to have missed the point about artisan food production.

“We are an endangered species,” says Silke Cropp. “The artisan is always going to be quite a small producer. Artisan to me means hand-made using raw and first-class, quality ingredients, putting expensive stuff together to make something as best as you can, that people will talk about as something fabulous you can only get in Cavan or Kerry or Waterford.”

“Quality is such an obvious thing,” says Kevin Sheridan in

his role as Chair of the Taste Council, a Bord Bia initiative. “It brings the

producer and the customer together in a unique way, especially when people are

able to taste the product.

“Quality is such an obvious thing,” says Kevin Sheridan in

his role as Chair of the Taste Council, a Bord Bia initiative. “It brings the

producer and the customer together in a unique way, especially when people are

able to taste the product.

“One of the first things I organised with the Taste Council was an organoleptic seminar for Irish cheese-makers. We got them together to talk about taste, nobody else was talking about the quality of taste.”

This, he says, is because we do not value our food.

“We are told we must buy food cheaper. We go for the cheapest food and this is not replicated in other sectors.

“Our food culture is of utmost importance economically, socially, culturally, so let’s get a co-ordinated approach to look at it, to grow it. That’s how seriously it needs to be taken because it benefits every area: employment, rural development, tourism, health, the landscape, our environment. It is so important on every level.

“Somebody needs to say: ‘Hold on. If you take Food Harvest 2020 to its conclusion, with its one vision mindset of Irish agriculture and an economic model focused on commodity export, you’ll have 20 landowners owning the whole of Ireland with mass food production’.”

Aldi, Lidl and Tesco have been actively promoting Irish produce but seem unable to know how to sell artisanal foods. It is not unusual to see them languishing on the reduced shelf.

Despite being reduced from €2.49 to €1.84 then to €1.34, 250g of Sunstream tomatoes grown in County Waterford sat on the shelf in Letterkenny Tesco. The Bord Bia Quality Assurance Scheme with its Origin Ireland logo made little difference, not surprising when imported tomatoes cost less. Yet these delicious tomatoes have the flavour and taste of any similar tomato grown in Provence or the Tuscan hills, a truly remarkable feat by the Waterford grower.

The Tesco Cheeses of Ireland brand is a great marketing innovation. When 150g of old Irish creamy blueberry costs €3.19 (€20.20 a kilo) only a cheese connoisseur will appreciate the effort.

Aldi has made a better job than Lidl with its range of artisan cheeses, simply by putting better information on its packaging and identifying the product as Irish and home-made.

According to Kevin Sherdian, this is a crucial problem. Irish people in general are not being educated to appreciate food of quality and do not recognise it when they see it. Saying it is Irish and home-made is not enough.

Despite their perceived loyalty to Irish produce, supermarkets are not interested in artisan and small-scale produce. “There is no benefit to them selling branded products,” he says. “The only reason they do is to control the supply chain.”

Critics of Food Harvest 2020 and the direction big business is taking Irish food production are few and far between, and Kevin Sheridan wonders what can be done to raise the profile of genuine small-scale production.

“We need diversity but instead of trying to make one cheese company ten times bigger, we need ten cheese companies. By its nature, small food production is labour-intensive and therefore creates more jobs.

“To shape our food culture without the supermarkets is not impossible but it can’t be done without them. The biggest problem is not innovation, it is route to market and you need to create demand.”

When distributors want to impose high mark-ups and supermarkets prefer to pay after 90 days, direct selling online and via market stalls relies on reputation, which in turn is influenced by image.

Food Harvest 2020 sees a small role for artisan food but it is obvious to Sheridan that nothing will happen unless the small producers take the initiative themselves.

“Probably the hardest people to get to work together unfortunately are the food artisans because they are so individualistic but it is also hard to see how they could do it on their own.

“Certainly, small co-ops have to be part of the potential for the growth of this industry. There is plenty of room for development. The food community need to come together because we are looking at only one model for food production.”

Advocates of artisan production agree that a visual infrastructure needs to be built (with advertising, road and street signs, and maps indicating where the food producers, food fairs and markets, food tours and food demonstrations are to be found) allied to promotional campaigns that put artisan food firmly in the public eye.

You can’t mistake Silke Cropp’s unique cheese as anything but artisanal, it’s as pretty as her idyllic setting in rural Cavan.

Food Markets

MARKETS provide producers with loyal customers who give valuable feedback and suggestions for new products.

They are essential in guaranteeing regular cash flow.

Markets that sign up to the ‘Good Practice Standard’ administered by Bord Bia and the department undertake to stock artisanal produce and accommodate seasonal produce.