29 April 2014 Edition

Commemoration, memory and history

History, not only in Ireland but elsewhere, is always contested, no doubt because history is less about facts and always about interpretation

WHO remembers Slobodan Milosevic? He was a hero to some; to others he was ‘The Butcher of the Balkans’, the person who brought genocide and slaughter back to Europe after the Nazi atrocities earlier in the 20th century.

Milosevic was a Serb, bent on eliminating all non-Serbs through massacre and rape. Eight thousand Bosnian Muslims were killed in Srebrenica. Milosevic stirred Serbian nationalism and violence through the manipulation of commemoration.

Within Serbia there was Kosovo. Its population was 85% Albanian, with only 194,000 Serbs who had the better jobs, housing and social privileges. Milosevic invoked memory of the Battle of the Blackbirds Field in 1389. There was already a Serbian national festival but not of the defeat of the Serbs by the Ottoman Empire as it moved into Europe. There was selective memory.

Mainly through songs, the commemoration honoured a Serb, Milosh Obravitch, who in 1389 had made his way into the Ottoman Sultan’s tent and stabbed the Sultan repeatedly to death. The reality was that in 1389 the Serbs had been totally humiliated by the Ottomans. Whatever songs were sung about Obravitch, the humiliating defeat lived long in the memory. In effect, Milosevic was repeating, ‘Remember 1389, remember Kosovo’. Serbian nationalists were also Eastern Orthodox and their nationalism and religion were deeply intertwined. The 600th anniversary of the humiliating defeat at the Battle of the Blackbirds Field was in 1989, and Milosevic made full use of it. The result introduced new words to our vocabulary such as “ethnic cleansing”, in reality mass murder. Milosevic invoked memory and commemoration for very violent purposes.

Was Milosevic really concerned with history or were his actions in relation to commemoration due to psychology? J. M. Roberts, the historian, has said: “It is only psychology which gives a special tone to centenary events” (Penguin History of Europe, p644).

A few years ago I was in Sarajevo presenting a paper at a conference on Healing and Memory. I remember the visit well for two reasons.

Thanks to an Icelandic volcanic ash cloud and the closure of much of European airspace, I was stuck in Sarajevo. The other memory was on the afternoon cultural tour of the city, still bearing all the marks of devastation following the conflict of the early 1990s and some 30,000 dead. During a visit to a Serbian Orthodox Church, the priest was relating his story of the conflict when a three-way argument developed between the tour guide, the interpreter and the priest. We stood and listened to three different versions of the recent 1990s. Whatever the other Europeans made of it, I felt very much at home!

History, not only in Ireland but elsewhere, is always contested, no doubt because history is less about facts and always about interpretation. The tendency is to read the past through the lens of the present and present needs. It may be the need to dominate the other, to establish one’s narrative as norm over the other, or to interpret history from the perspective of our current fears, anxieties and angst. Commemoration may have more to do with the present than the past. In this sense it has more to do with psychology than with history.

If the word celebration is used of past events in our history, then part of the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition is “to perform a religious ceremony”. This is why high commemorative events have a religious dimension, or a pseudo-religious dimension. The deity or god is directly invoked or the ceremony is highly ritualised, a solemn or sacred occasion with an underpinning spirituality. Especially if the commemorative event recalls war or violence, then it has to be invested with the highest moral authority. If people are being sent out to kill in war and conflict, and to be killed, then those in charge have to invoke the highest moral authority. In the Western world, that is usually God (whatever we mean by ‘God’). Commemorations are often ritualised ceremonies, quasi-sacred occasions with a religious or pseudo-religious dimension. Such religious or ritualised ceremony may need rigorous moral and ethical critique. It may indeed have more to do with psychology than history, memory, religious or moral reality.

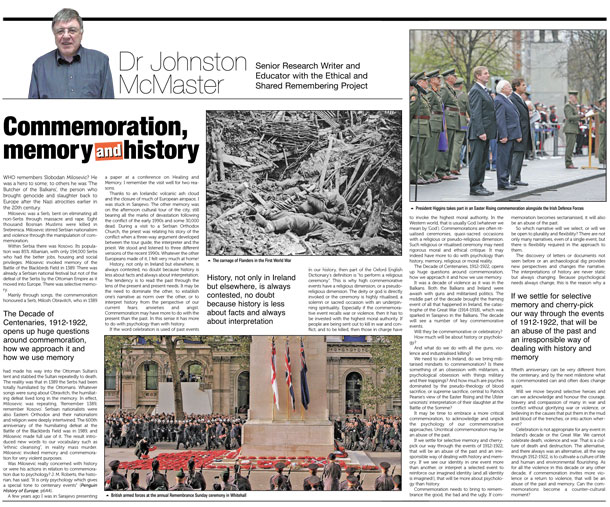

• President Higgins takes part in an Easter Rising commemoration alongside the Irish Defence Forces

The Decade of Centenaries, 1912-1922, opens up huge questions around commemoration, how we approach it and how we use memory.

It was a decade of violence as it was in the Balkans. Both the Balkans and Ireland were awash with guns and militarised politics. The middle part of the decade brought the framing event of all that happened in Ireland, the catastrophe of the Great War (1914-1918), which was sparked in Sarajevo in the Balkans. The decade will see a number of key commemorative events.

Will they be commemorative or celebratory?

How much will be about history or psychology?

And what do we do with all the guns, violence and industrialised killing?

We need to ask in Ireland, do we bring militarised mindsets to commemoration? Is there something of an obsession with militarism, a psychological obsession with things military and their trappings? And how much are psyches dominated by the pseudo-theology of blood sacrifice, or supreme sacrifice, central to Patrick Pearse’s view of the Easter Rising and the Ulster unionists’ interpretation of their slaughter at the Battle of the Somme?

It may be time to embrace a more critical commemoration, to acknowledge and unpick the psychology of our commemorative approaches. Uncritical commemoration may be an abuse of the past.

If we settle for selective memory and cherry-pick our way through the events of 1912-1922, that will be an abuse of the past and an irresponsible way of dealing with history and memory. If we see our identity in one event more than another, or interpret a selected event to reinforce our imagined identity (and all identity is imagined!), that will be more about psychology than history.

Commemoration needs to bring to remembrance the good, the bad and the ugly. If commemoration becomes sectarianised, it will also be an abuse of the past.

So which narrative will we select, or will we be open to plurality and flexibility? There are not only many narratives, even of a single event, but there is flexibility required in the approach to them.

The discovery of letters or documents not seen before or an archaeological dig provides new perspectives and changes the narrative. The interpretations of history are never static but always changing. Because psychological needs always change, this is the reason why a fiftieth anniversary can be very different from the centenary, and by the next milestone what is commemorated can and often does change again.

Will we move beyond selective heroes and can we acknowledge and honour the courage, bravery and compassion of many in war and conflict without glorifying war or violence, or believing in the causes that put them in the mud and blood of the trenches, or into action wherever?

Celebration is not appropriate for any event in Ireland’s decade or the Great War. We cannot celebrate death, violence and war. That is a culture of death and destruction. The alternative, and there always was an alternative, all the way through 1912-1922, is to cultivate a culture of life and human and environmental flourishing. As for all the violence in this decade or any other decade, if commemoration invites more violence or a return to violence, that will be an abuse of the past and memory. Can the commemorations become a counter-cultural moment?

• Dr Johnston McMaster is Senior Research Writer and Educator with the Ethical and Shared Remembering Project