29 April 2014 Edition

Drivers of the revolution

These two men, more than any others, put in place the elements that ensured that there would be a Rising in 1916

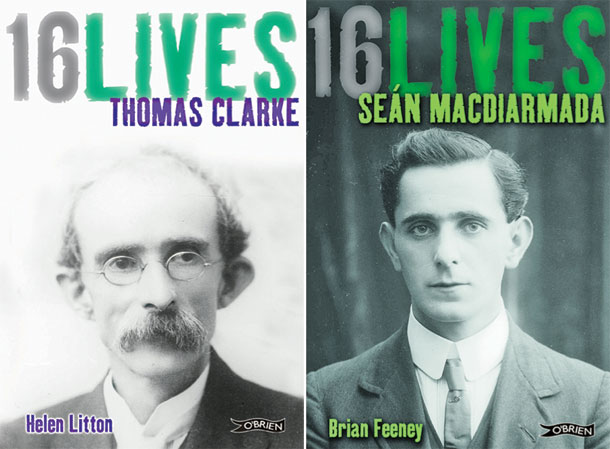

Thomas Clarke

By Helen Litton

Seán Mac Diarmada

By Brian Feeney

16 Lives series, by O’Brien Press

BOOKS REVIEW BY MÍCHEÁL Mac DONNCHA

AT CHRISTMAS 1915, 22 people gathered for Christmas dinner at the home of veteran Fenian John Daly in Limerick.

Among the guests were John Daly’s niece and nephew, Kathleen Clarke and Edward Daly; his old comrade Tom Clarke, who was Kathleen’s husband; and their friends Con Colbert and Seán Mac Diarmada. Within six months of that Christmas dinner, four of those present (Con Colbert, Edward Daly, Tom Clarke and Seán Mac Diarmada) were executed in Kilmainham Jail by British Army firing squads.

The latest two books in the superb 16 Lives series on the executed leaders of 1916 are the biographies of two of that group that gathered in Limerick: Tom Clarke and Seán Mac Diarmada.

Without question, these two men were the drivers of the revolution because they, more than any others, put in place the elements that ensured that there would be a Rising in 1916.

These are contrasting but complementary biographies.

In his study of Seán Mac Diarmada, Brian Feeney naturally emphasises the political, given that Mac Diarmada was totally consumed by his commitment to the republican struggle. Helen Litton places more emphasis on Tom Clarke’s family life, using his correspondence and the memoirs of Kathleen. But, of course, Clarke was just as committed as Mac Diarmada and family came second to Ireland, as Kathleen, a staunch republican in her own right, frankly admitted.

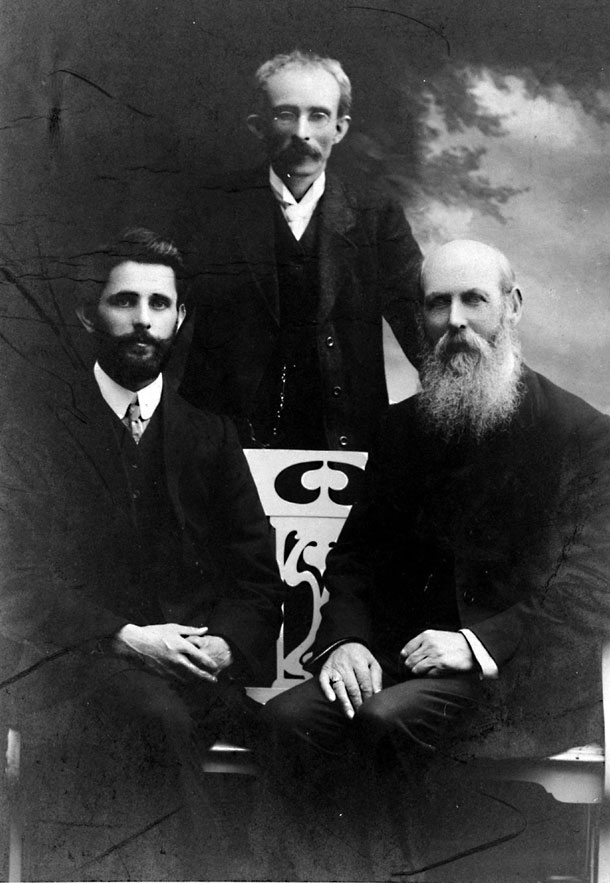

• Seán Mac Diarmada, Thomas Clarke and the veteran Fenian John Daly, who served time in prison with Clarke

Helen Litton provides a vivid portrait of Clarke, making clear his absolute determination to strike a successful blow for Irish freedom. During his long years in English prisons he saw his comrades die prematurely and go mad under the punitive regime. He also saw how the Fenian movement was divided by splits and many of its activities compromised by spies and informers.

Did all this make him bitter and motivated by a desire for revenge against Britain? The author concludes that it did and disagrees with previous authors who say he was without bitterness. It is impossible to know what his inner thoughts were as he wrote little and spoke relatively rarely in public. But I find myself agreeing with the earlier writers and concluding that, on balance, Clarke’s prime motivation must have been a positive one – deep patriotism, love of country and desire for freedom. There is no trace of bitterness in his Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life.

Clarke and Mac Diarmada were expert conspirators, implementing the original Fenian idea of a conspiratorial network of committed activists well-prepared to strike at an unsuspecting British regime in Ireland at the opportune moment.

Together they revived the Irish Republican Brotherhood. When necessary, they kept even some of their senior IRB colleagues (like Denis McCullough of Belfast) in the dark about their plans. Their tight secrecy and control ensured that the preparations for the Rising were not compromised by spies or informers.

• A young Thomas Clarke

But conspiracy has its limits. It created a dichotomy in the Irish Volunteers between IRB and non-IRB officers. It added to the confusion in the days leading up to the Rising when the elaborate plans of Clarke and Mac Diarmada began to unravel with the capture of the German arms ship, the arrest of Roger Casement and Eoin Mac Neill’s disastrous countermanding order.

That Clarke and Mac Diarmada, amidst all this welter of confusion and dismay, kept their heads and drove on with the Rising, speaks volumes of their determination and courage and that of the other leaders and of the rank and file of the movement.

The republican leaders planned for a successful Rising, not for a blood sacrifice. All the scholarship of recent years confirms that, and this is also reflected in these books. The plans for the Rising are better understood, especially since more information has become available from the Bureau of Military History accounts of veterans. But the leaders also saw that it was vital for the morale and self-respect of the Irish people that a blow for freedom was struck at that time. The ‘Great War’ (First World War) was at its height; it could conclude at any time with victory for either side; there would be an international peace conference and how could Ireland make any case if she had done nothing to assert her independence?

The centenary of the start of the First World War is already seeing a revival of British imperial propaganda, including the myth that the war was fought “for the freedom of small nations”. The British Imperial Government fighting “for freedom” gave to our small nation the execution of the leaders in 1916, mass imprisonment, censorship and repression, the attempt to enforce conscription, the refusal to recognise the will of the people in the 1918 general election and the banning of Dáil Éireann. Clarke and Mac Diarmada and their comrades ensured that the Irish people rose again and took on that Empire and its lies.

• A group of Irish Volunteer officers pose for a photo in Cork, 1915, with Seán Mac Diarmada seated third from the left