12 January 2014 Edition

Nelson Mandela – A hero among heroes

‘Terrorist’, political prisoner, peacemaker, international icon

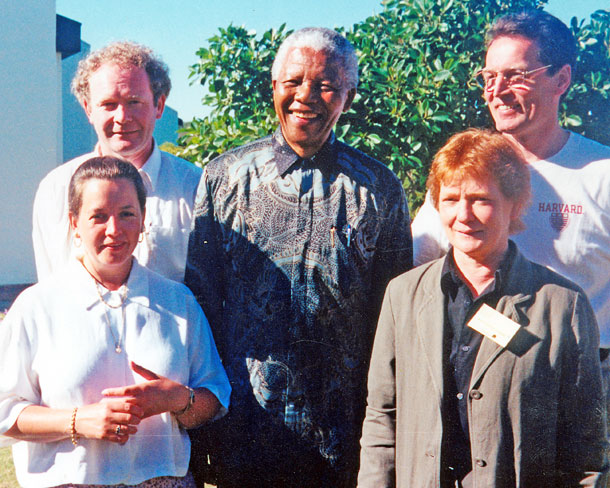

• 1997 Irish Peace Process inter-party talks at the Cape in South Africa: Nelson Mandela with (clockwise) Sinn Féin’s Siobhán O’Hanlon, Martin McGuinness, Gerry Kelly and Rita O’Hare

It would be unrealistic and wrong for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force – Nelson Mandela

NELSON MANDELA spent his entire life fighting against the injustice and inequality of the tyrannical, white-supremacist, apartheid regime in South Africa. He was also an internationalist and close friend of Ireland and the Republican Movement.

Mandela grew up in the small village of Qunu in the Eastern Cape. In university he became increasingly involved in revolutionary, communist and African nationalist politics before co-founding the ANC’s Youth League on Easter Sunday 1944. Following the 1948 general election (in which only whites were allowed to vote) the ruling National Party threatened to implement extremely strict racial segregation in all aspects of South African life in a system that would become institutional apartheid. It was then that Mandela and other younger members of the ANC began to lobby for direct action against the racist government.

In 1956, Mandela was arrested and charged with “high treason” for his part in protests against the demolition of black suburbs of Johannesburg. After a six-year trial he was found not guilty.

In 1961, he co-founded the armed organisation Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), better known as MK. In its manifesto, MK said the African people had been left with two options: submit or fight.

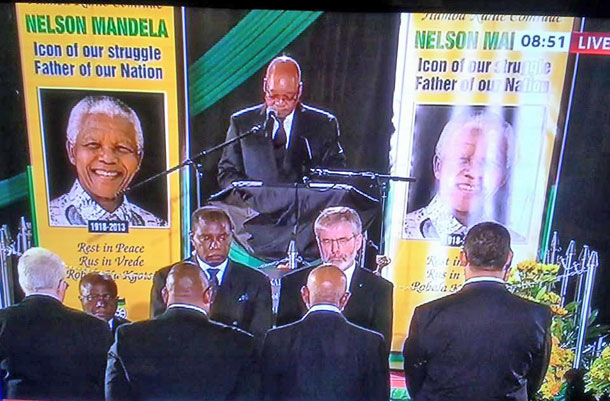

• Gerry Adams and Richard McAuley in the international guard of honour alongside Mandela’s

The MK manifesto declared:

“We have no choice but to hit back by all means in our power in defence of our people, our future, and our freedom.”

Explaining his reasoning to engage in armed struggle, Madiba (Mandela’s Xhosa clan name) said it was the only option left to anti-apartheid activists:

“It would be unrealistic and wrong for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the government met our peaceful demands with force.”

MK launched a series of bomb and sabotage attacks against government facilities and was quickly banned as a “terrorist organisation”. The organisation would go on to receive military training and military assistance from the IRA, most notably in the 1980 bombing of the regime’s Sasol Oil Refinery to coincide with the apartheid state’s Republic Day celebrations.

In 1962, Mandela was arrested again and stood trial along with nine other ANC leaders. He was charged and convicted on four charges which included one of attempting to initiate a guerrilla war to overthrow the racist regime. He was sentenced to life imprisonment. In his speech from the dock, he said:

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

He would spend his next 18 years imprisoned on Robben Island, used for forced labour. During this time he and his prison comrades were subjected to assaults and beatings by white prison wardens. During his incarceration he was refused parole to attend either the funeral of his mother Nosekeni or of his son Thembi, who died in a car crash. He maintained his international perspective and he and fellow ANC prisoners followed closely the Irish republican Hunger Strike of 1981 and honoured all of those who died. On Madiba’s calendar on 5 May 1981 is handwritten: “IRA martyr Bobby Sands dies.”

• Martin McGuinness, Nelson Mandela and Gerry Adams meet in Dublin in April 2000

In 1985, South Africa’s apartheid dictator PW Botha, faced with a critical security situation, offered Mandela release from prison but only if he unconditionally rejected violence as a weapon of political change. Mandela rejected the offer.

After Botha suffered a stroke, his succesor, F. W. de Klerk released 71-year-old Mandela and legalised all formerly outlawed parties.

Addressing crowds in Dublin in 1990 (Dublin was the first capital city in the world to grant him Freedom of the City status) and also the Oireachtas, he said that the people of Africa, and the people of Ireland “should be free to govern themselves and to determine their destiny”.

Mandela’s staunch support for the Republican Movement led to senior Ulster Unionist Party politician Frank Millar describing him as a “black Provo”. During a meeting with Gerry Adams in South Africa on the 20th anniversary of the 1981 Hunger Strike, Mandela described Sinn Féin as “an old friend and ally” for supporting us “very strongly during the anti-apartheid struggle”.

In 1995, the ANC invited senior members of Sinn Féin to South Africa to discuss a peace process in Ireland. The British Government lobbied hard to stop the meeting. Mandela, then elected president by a landslide in the first free and democratic elections in South Africa, defied them, having his photo taken shaking Gerry Adams’s hand. Many more meetings between the ANC and Sinn Féin took place throughout the following years in both Ireland and South Africa. Former MK activists even came to Ireland to visit republican POWs in prison to discuss the negotiations and tactics.

As the media continues to debate and wrestle with Mandela’s legacy, for oppressed people across the globe he will continue to be an inspiration.