1 December 2013 Edition

Language, resistance and revival: The importance of culture in struggle

‘Language isn’t just about the spoken word . . . it is about the way people see themselves in the world; it is about identity’

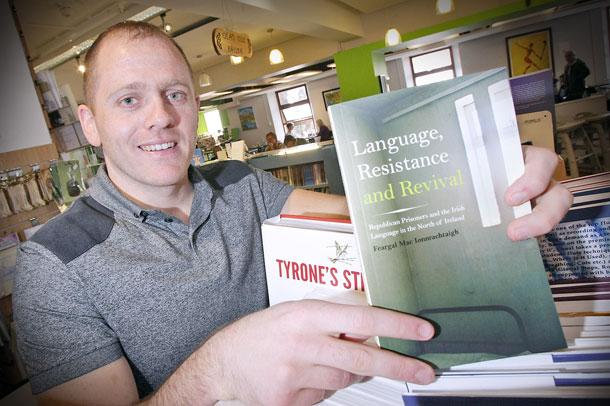

• Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh

‘Colonialism imposed its control of the social production of wealth through military conquest and subsequent political dictatorship. But its most important area of domination was the mental universe of the colonised, the control through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relationship to the world. Economic or political control can never be complete without mental control’ – Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Kenyan anti-colonial writer

PEADAR WHELAN, a former political prisoner who learned much of his Irish in Long Kesh, opens up a challenging debate on the back of the recent publication of Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh’s new book, Language, Resistance and Revival: Republican Prisoners and the Irish Language in the North of Ireland.

The subject of the book is the revival of the Irish language and the importance of the republican prisoners in that revival but, Peadar Whelan argues, it develops “a polemic around resistance and revival tied into our struggle against Britain’s rule in our country over the centuries”.

THERE ARE powerful forces in the political and media establishments as well as an apathetic attitude to the language in society at large and the education system in particular which make the task of promoting Irish very difficult.

Opposition and the barriers to the Irish language have to be seen in the context of Britain’s colonial domination and destruction of the Irish language and culture as a central part of its subjugation of the Irish nation.

For republican prisoners, whether they were imprisoned in Frongoch after the Easter Rising of 1916, through the fallow years for republicanism after the Civil War to the Cages of Long Kesh and the prison protest that took place in the H-Blocks and Armagh Women’s Prison, education was always political. Speaking and promoting Irish is always political.

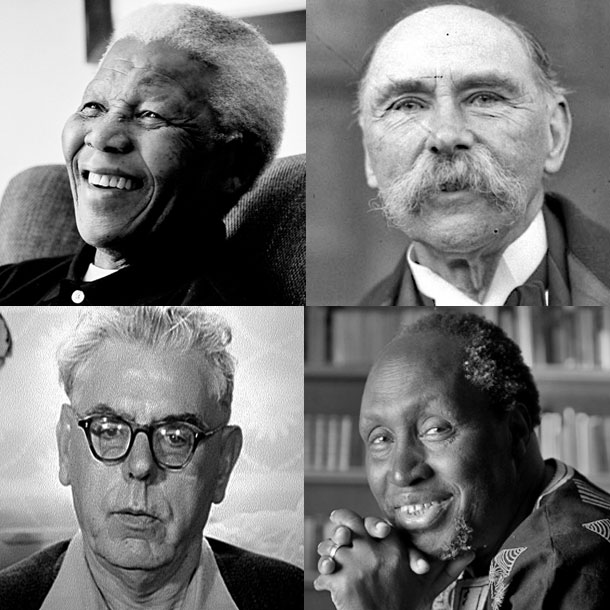

In his introduction to Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh’s book, Phil Scraton of Queen’s University School of Law quotes Nelson Mandela.

Speaking of his time on Robben Island, Mandela says:

“The challenge for every prisoner, particularly every political prisoner, is how to survive prison intact, how to emerge from prison undiminished, how to conserve and even replenish one’s beliefs.

“The first task in accomplishing that is learning exactly what one must do to survive. To that end, one must know the enemy’s purpose before adopting a strategy to undermine it.

“Prison is designed to break one’s spirit and destroy one’s resolve. To do this the authorities attempt to exploit every weakness, demolish every initiative, negate all signs of individuality – all with the idea of stamping out that spark that makes each of us human and each of us who we are.”

Nelson Mandela’s words go to the heart of the narrative of Mac Ionnrachtaigh’s book.

The revival of the Irish language and promotion of Irish culture is, for me, about challenging a globalised pop culture that is essentially about cloning people and societies, killing what makes each of us human and turning nations into repositories of dominant ideologies.

This is most obvious in the way the media in Ireland interprets international events through the prism of a dominant western worldview.

Many people are infatuated with the lives of sports and pop or TV and movie stars and media ‘celebrities’. It is more ‘cool’ now to call your child Tyler rather than Tomás as parents bow to the world of soap opera grandiosity.

At a supposed ‘high-brow’ level we have revisionist Ruth Dudley-Edwards attacking Ken Loach over his film The Wind That Shakes the Barley, saying that “as empires go, the British version was the most humane of all. With all its deficiencies, it brought much of value to most of the countries it occupied”.

Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh, quoting Kenyan anti-colonial writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, describes this psychological process as “the most important area of domination”.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o, in his Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, writes:

“Colonialism imposed its control of the social production of wealth through military conquest and subsequent political dictatorship. But its most important area of domination was the mental universe of the colonised, the control through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relationship to the world. Economic or political control can never be complete without mental control.”

In his Wretched of the Earth, Franz Fanon talks of this as assimilation.

He maintains that in those colonies where the “colonised people” found themselves “face to face with the language of the civilising nation; that is with the culture of the mother tongue”, this assimilation was at its most relevant and manifested itself in the imperial education system, where control of language epitomised the hierarchical power structures of colonialism.

Writing in 1892, Douglas Hyde, the founder of the Gaelic League, identified the crucial connection between the need to revive the language and deanglicisation as steps towards decolonisation:

“I have no hesitation at all in saying that every Irish-feeling Irishman who hates the reproach of West-Britonism should set himself to encourage the efforts which are being made to keep alive our once great national tongue. The losing of it is our greatest blow and the sorest stroke that the rapid anglicisation of Ireland has inflicted upon us. In order to deanglicise ourselves we must at once arrest the decay of the language.”

Both the Gaelic League and the GAA, according to Mac Ionnrachtaigh, “envisaged the emancipation of the Irish poor from the ‘dehumanisation, degeneracy and depoliticisation’ of existing athletics clubs”.

This deliberate project of decolonisation, asserts Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh in Language, Ideology and National Identity, was designed to undo “the shame of defeat, dispossession, humiliation and impoverishment the classic colonial condition”.

This enhanced interest in “nationalist ideas”, as Mac Ionnrachtaigh labels them, also coincided with a developing interest in socialist ideology and labour politics, as exemplified by James Connolly and Jim Larkin.

According to Mac Ionnrachtaigh, Connolly drew inspiration from the past and argued for a united ideological front that would enable the reconquest of Ireland in the future based on what he viewed as the culture, fellowship and co-operative ideals of Gaelic civilisation.

When the Easter Rising took place in April 1916, the link between the Rising and the Gaelic League was underpinned by the fact that six of the seven signatories of the Proclamation were members and all but two of the League’s Coiste Gnótha were involved in the Rising.

That the Rising is universally recognised as a defining moment in the Irish revolution is beyond doubt, while Russell Rees argues in Ireland between 1905 and 1925 that “the Gaelic resurgence was the revivifying force which made possible the Easter Rising”.

Sadly, in the aftermath of the Civil War and the defeat of radical republicanism, any hope that the language and the wider cultural revival would flourish were dashed.

Writing in An Phoblacht in 2006, Sinn Féin’s Aengus Ó Snodaigh maintained that, despite the genuine efforts of language enthusiasts to promote Irish in the newly-formed state, “the unionist ascendancy and a pro-British, colonial mentality retained control of most state institutions”, thus enshrining the hegemony of a reactionary Free State.

• (clockwise from top left) South African revolutionary Nelson Mandela, Irish-language scholar Douglas Hyde, Kenyan anti-colonial writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Irish-language writer Máirtín Ó Cadhain

In the North, unionist hostility, past and present, is summed up by Liam Andrews in his The Irish Language in the Education System of Northern Ireland: Some Political and Cultural Perspectives.

He maintains that the unionists have viewed the Irish language and those advocating its revival as a threat, as an “anti-British counter-culture dominated by republican separatists” and that promoting Irish was “sedition and disloyalty under another name”.

Of course, “sedition and disloyalty” are badges of honour for republicans and the unresolved national question saw many people imprisoned during the different phases of struggle against partition.

And for those in prison, resistance and education went hand in hand.

Learning Irish was central to that not least because of republicans’ commitment to the language. It was also part of a process of conscientisation, of becoming aware that the British imperialist project involved military, political, economic and cultural strategies.

That the educational experiences of republican prisoners inspired unprecedented numbers of people to learn Irish is testament to their resistance and their commitment to change.

Setting the Irish language in the context of colonisation/decolonisation underpins the political ideological imperative for its revival.

Language isn’t just about the spoken word; it is about the way people see themselves in the world; it is about identity.

Former Curragh internee and Irish language teacher Máirtín Ó Cadhain in his often-quoted phrase says:

“Is í athgabháil na Gaeilge, athgabháil na hÉireannagus í athgabháil na hÉireann slánú na Gaeilge.”

The reconquest of Irish is the reconquest of Ireland and the reconquest of Ireland is the salvation of Irish.

Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh at art installation Teanga-Aisling an Phobail on Belfast's Falls Road.

The piece welcomes visitors to the Gaeltacht Quarter and celebrates the Irish language. It speaks of a resilient and compassionate community full of hope and optimism. A people as strong as the stone.

The imposing stone labyrinth is inspired by the St Brigid's cross and stands in a pocket park adorned with Belfast place names from Ráth Cúile (Rathchoole) to Bóthar Seoighe (Shaws Road).

Artist Robert Ballagh and architect Ciarán Mackel collaborated with Irish-American artist Brian O'Doherty in the creation of the work.

Language, Resistance and Revival:

Republican Prisoners and

the

Irish Language in the North of Ireland

by Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh.

Published by Pluto Press.

Available through Pluto and the author as well as

An Ceathrú Poilí in Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich,

216 Bothár na Bhfál, An Cheathrú Ghaeltachta, Béal Feirste, BT12 6AH.

See also: An Ghaeilge i Long Kesh, le Séanna Breatnach, An Phoblacht, Deireadh Fomhair 2012