3 November 2013 Edition

The centenary of the Irish Volunteers – Óglaigh na hÉireann

Remembering the Past

‘Ireland unarmed will attain just as much freedom as it is convenient for England to give her; Ireland armed will attain ultimately just as much freedom as she wants’

THE FOUNDING of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913 was a momentous event that would help determine the course of Irish history for decades to come. Yet the circumstances which brought about the birth of the Volunteers were very particular to the time and they arose out of the immediate political crisis around Home Rule for Ireland.

The political background to the formation of the Irish Volunteers was the violent Tory and unionist reaction against Home Rule. The Tories (official name ‘The Conservative and Unionist Party’, often simply ‘The Unionist Party’) seized on Home Rule as the main political front on which to fight the British Liberal Party government which they detested for its reforming agenda. In 1912, the Ulster unionists under Edward Carson and James Craig had pledged to form a provisional government as soon as Home Rule became law.

By the time of the Ulster Covenant in September 1912, arms were already being imported in large numbers. The pro-British Ulster Volunteer Force was formed and was financed, armed and officered with the help of the English and Scottish Tories.

The Unionist Northern Whig newspaper wrote in June 1913:

“The prudence of proceeding quietly with the business of gun-running was self-evident. Rifles – and not only rifles but machine guns and a large quantity of ammunition – have reached Ulster from many sources and under many aliases.”

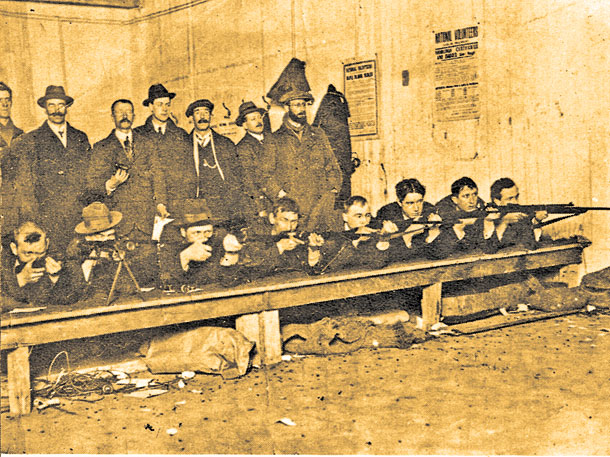

• Irish Volunteers in training

This raised the question of how Irish nationalists should respond. John Redmond and the Irish Party at Westminster placed their trust in the Liberal Government to face down the Tory and unionist rebellion and to ensure that Home Rule came into operation on schedule in 1914. However, many nationalists (and not just the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the IRB) believed that this was not sufficient and that Ireland needed an armed force to vindicate her right to self-government and to act as a counter-weight to the Tory/unionist threat.

The separatists of the IRB – while recently reorganised by Tom Clarke, Seán Mac Diarmada and Bulmer Hobson – were not strong enough on their own to establish an open Irish Volunteer organisation. But they had influence in nationalist organisations and the advantage of their own tightly-disciplined organisation.

The prospect that Home Rule night be thwarted by the Tory/unionist rebellion had the effect of radicalising many nationalists such as Pádraig Mac Piarais, who spoke from a Home Rule platform in Dublin in 1912 and said that if they were cheated again by England there would be “red war throughout Ireland”.

While Mac Piarais would go to play a pivotal role, the key man in the formation of the Volunteers was Michael O’Rahilly, known as ‘The O’Rahilly’.

O’Rahilly had refused to join the IRB, telling Constance

Markievicz that the only secret society he would join would be one in which

every member was required to have a rifle and a thousand rounds of ammunition.

He preferred to work in open organisations such as Conradh na Gaeilge and Sinn

Féin, in which he was very active. In 1912, O’Rahilly wrote a series of articles

for the IRB paper, Irish Freedom, on the need for an Irish army.

O’Rahilly had refused to join the IRB, telling Constance

Markievicz that the only secret society he would join would be one in which

every member was required to have a rifle and a thousand rounds of ammunition.

He preferred to work in open organisations such as Conradh na Gaeilge and Sinn

Féin, in which he was very active. In 1912, O’Rahilly wrote a series of articles

for the IRB paper, Irish Freedom, on the need for an Irish army.

“In the last analysis, the foundation on which all government rests is the possession of arms and the ability to use them,” he wrote.

By early 1913, O’Rahilly, Eamonn Ceannt, Cathal Brugha and others in Sinn Féin were carrying out organised arms training in Dublin. In July, on the proposal of Bulmer Hobson, IRB members were drilling in 41 Parnell Square under instruction from officers of Fianna Éireann, the republican boy scouts.

While the exact sequence of events is disputed (some claim Hobson later exaggerated his own role), it is agreed that the impetus for the public call for the formation of the Irish Volunteers came when Professor Eoin Mac Néill of University College Dublin, a prominent Conradh na Gaeilge member and nationalist, was approached to write an article on Ulster for the Conradh newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis.

The paper’s manager was O’Rahilly and it was he who asked Mac Néill to write the article, The North Began (1 November 1913). It excoriated the Tory/unionist rebellion and said “it appears that the British Army cannot now be used to prevent the enrolment, drilling and reviewing of Volunteers in Ireland”.

Coming from Mac Néill, a supporter of Redmond, this call appealed to nationalists beyond the separatists of the IRB, just as the IRB wished it to do. The following week, O’Rahilly published an article from Mac Piarais who wrote: “Ireland unarmed will attain just as much freedom as it is convenient for England to give her; Ireland armed will attain ultimately just as much freedom as she wants.”

Two days after that article appeared, O’Rahilly sent out invitations to a meeting in Wynn’s Hotel, Abbey Street, on 11 November. Among those attending were Mac Néill, Mac Piarais, O’Rahilly, Mac Diarmada, Éamonn Ceannt and Piaras Beaslaí.

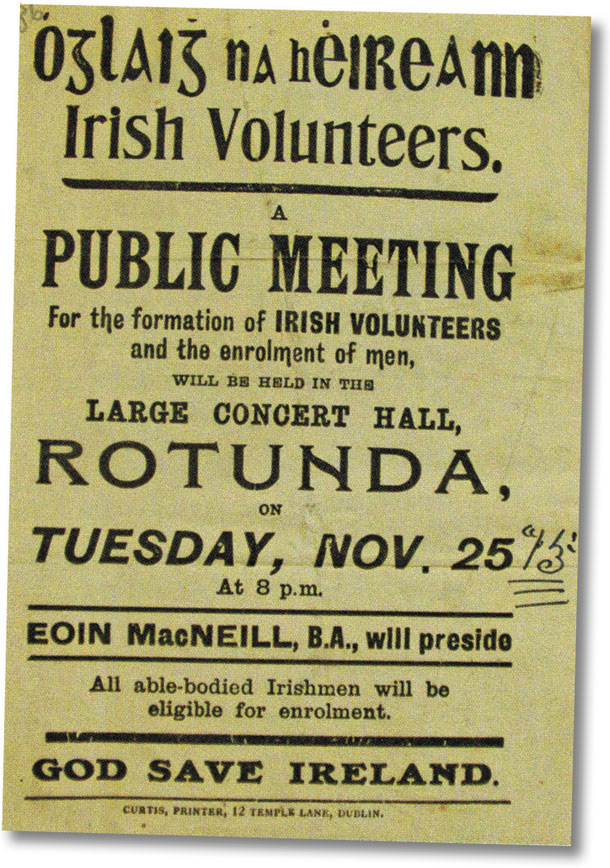

On 25 November, a public meeting for the formation of Irish Volunteers was held in the Rotunda. The Lord Mayor of Dublin, Lorcan Sherlock, had refused the use of the Mansion House. The meeting was held in the Rotunda Rink, a building which held 4,000 people; there was an overflow crowd of 3,000 outside. The call for Volunteers had succeeded beyond all the expectations of the organisers. The manifesto adopted on the night began by stating that the Tory/unionist alliance planned to “make the display of military force and the menace of armed violence the determining factor in the future relations between this country and Great Britain”.

This was no empty accusation. Just three weeks earlier, the UVF had held an armed training camp of over 5,000 men at Baronscourt, County Tyrone, estate of the Duke of Abercorn. Leading English Tories such as F. E. Smith continued to stir up sectarianism and resistance to Home Rule. A week before the Rotunda meeting, he said in Manchester:

“You can put the whole of the Unionist Party in prison if you dare. We will see what happens if this quarrel is to be fought out on that level.”

Despite this, the Irish Volunteers made clear that they wanted no confrontation with the UVF. Their demand was for Irish liberty and it was directed at the British Government. A key passage in their Manifesto read:

“The object proposed for the Irish Volunteers is to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland. Their duties will be defensive and protective, and they will not contemplate either aggression or domination.”

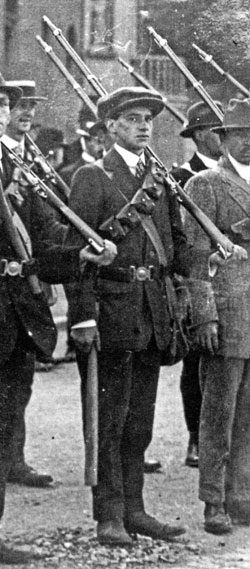

• The Irish Volunteers were founded in November 1913, a century ago this month.

• Crowds jostle for a view of Volunteers on parade in Cork City