5 August 2013 Edition

The Lockout’s legacy of struggle is needed now

Remembering the Past

Ranged on the side of the bosses were the British authorities: the police, the British Army, and the Catholic Church Hierarchy

AUGUST marks the centenary of the Great Lockout of 1913, when bosses in Dublin locked thousands of workers out of their jobs because the workers refused to sign a pledge not to join the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union.

In the article opposite, James Connolly asked how the challenge of the bosses would be met.

“Will we crawl back into our slums?” he asked.

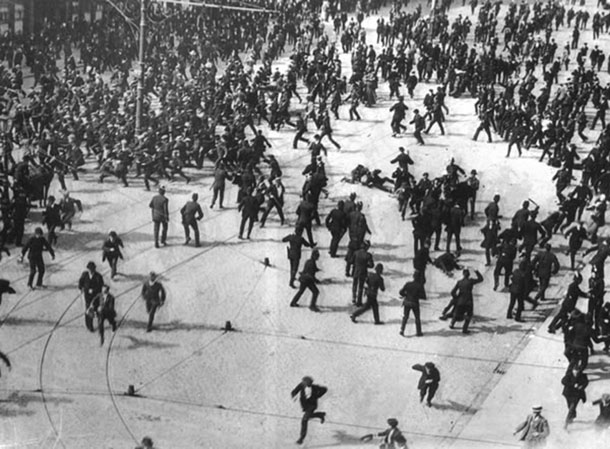

The organised workers of Dublin did indeed answer ‘No!’ (as Connolly predicted) and they entered a life or death struggle. On the very evening of the day that article appeared, two workers were beaten to death with batons by the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the next day the DMP attacked hundreds of workers as they defied the British Government ban on Jim Larkin’s mass meeting in O’Connell Street. It was Ireland’s first ‘Bloody Sunday’ of the 20th century.

Months of conflict followed. There were violent clashes on picket lines, riots and running battles between locked-out workers, police and strike-breakers. Armed forces of the British crown guarded strike-breaking operations. The DMP even attacked people in their tenement homes, smashing their meagre furniture as well as their heads.

• Constance Markievicz helped to feed the hungry at Liberty Hall in 1913

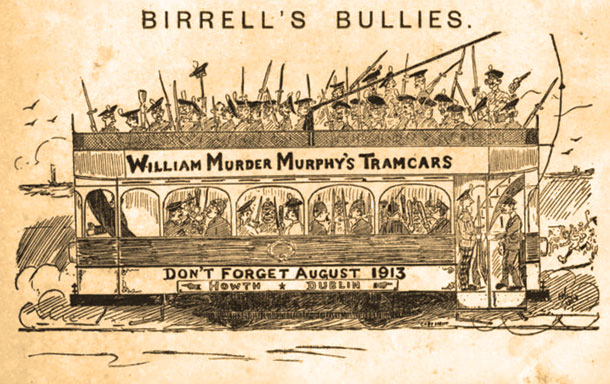

Ranged on the side of the bosses were the British authorities in Dublin Castle, the DMP, the Royal Irish Constabulary, the British Army, the ‘constitutional nationalists’ of John Redmond’s Irish Party, and the Catholic Church Hierarchy. The bosses’ leader was William Martin Murphy, wealthy capitalist owner of the tramway company, Independent Newspapers, the Imperial Hotel and other businesses.

Radical nationalists and republicans like PH Pearse, Tom Clarke, Thomas Ashe, Éamonn Ceannt , Thomas MacDonagh and Joseph Plunkett supported the workers. And the workers found natural allies in militant republican feminists whose campaign for the right to vote was at its height. Constance Markievicz worked to feed the hungry in Liberty Hall. Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, who had been on hunger strike the year before for women’s rights, was on hunger strike again with Connolly for workers’ rights in 1913.

The struggle closed in seeming defeat at the start of 1914. But the chief aim of the bosses – to break the ITGWU – had failed. The union, and trade unionism generally, flourished in the years after the 1916 Rising.

• Augustine Birrell was an English politician and Chief Secretary for Ireland in 1913

And, of course, the stream of struggle and resistance released by the Lockout flowed into the forces that made the 1916 Rising. The Irish Citizen Army, founded as a defence force in October 1913, was moulded by James Connolly into an armed vanguard of workers pledged to fight for a socialist Irish Republic.

Still today there are those who claim to be socialists but who deny Connolly’s lifelong teaching that Irish freedom and workers’ liberation are inextricably linked. Writing in the July/August issue of History Ireland, journalist and historian of the Lockout, Pádraig Yeates wonders if Irish workers “would have been better off fighting for socialism within the United Kingdom”!

The legacy of the Lockout for today is the fighting spirit of the Dublin workers led by Larkin and the principles and ideas of Connolly. That legacy of struggle is needed now more than ever to cut through apathy, individualism, greed and confusion; to build resistance against austerity and partition; and to propel a forward movement towards a New Republic.

• Dublin’s poor wait for food from a relief ship