28 April 2013 Edition

Bringing Ireland into line with the toxic world

Robert Allen wrote for An Phoblacht throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He will be occasionally reporting on north-west issues for An Phoblacht.

He is the author of numerous books, including Guests of the Nation (1990), Waste Not Want Not (1992), No Global (2004) and The Dioxin War (2004) about toxic issues and community opposition.

He is completing a fifth book on these issues, A Toxic Debate, about the conflict between Indaver and the Cork harbour communities. He is interested in hearing about any anti-toxic stories for inclusion in the book.

Robert Allen [email protected]

SOMETIME LATER THIS YEAR, a faceless bureaucrat will sign the documents to end five decades of community resistance. It’s a long war hardly known.

Time has already relegated the older battles to forgotten history. Monkstown, Nohoval, Barnahely, Finglas, Santry, Rathcoole, Clondalkin, Tallaght, Raffeen, Limerick, Ringaskiddy, Derry, Clarecastle.

The vanquished are hidden from scrutiny because only succeeding generations will know for sure whether their grandparents were right or wrong. A few skirmishes remain to be settled but the war is over. Ireland has been brought into line with the toxic world.

John Ahern, the Kilmallock-born general manager of Indaver Ireland, would tell you this is a harsh appraisal.

Indaver Ireland, a Flemish, Dutch-owned corporate that emerged out of the Dun Laoghaire waste management company Minchem Environmental Services, is providing the final solution to the hazardous waste problems that have terrorised successive governments, the state and local authorities since the late 1960s by offering an answer to the total waste question.

Six months ago, the communities thought they had won the war only to be told in the immediate aftermath of another victory that the battlefield had been moved, the rules of battle changed again, leaving the battle-weary insurgents left to wonder what they had to do to win. The war had gone onto yet another level.

The early battles were fought on terrain chosen by the communities and their allies. Their battlegrounds were in the open air, outside steel gates and on stone steps, or in the community hall, packed to the rafters with angry people unwilling to play by the hierarchical laws of the state or the demeaning rules of industry, intent on action that brought results. In Cork at first, then in Dublin, Limerick and Derry the belligerents gave no quarter and one by one the proposals for dumps and incinerators were defeated.

Enter Indaver

Twelve years ago, Indaver entered the game. They had the support of the Government. The Waste Management (Amendment) Act would pave the way for another attempt at the establishment of a national hazardous waste incinerator. And, unlike the previous attempts in Limerick and Derry, this one was serious.

Communities submitted 20,000 objections to Cork County Council as the debate about incineration and the need for a national hazardous waste solution gathered momentum. Despite the opposition that was growing in Cork, it was clear when the politicians came around to discussing incineration again during the Protection of the Environment Bill in February 2003, that the state had made up its mind. Fianna Fáil’s Martin Cullen effectively told the Seanad that incineration technology was infallible.

Linda Fitzpatrick is a mother who juggled her young children between the demands of the media as PRO for campaign group CHASE (Cork Harbour for a Safe Environment).

“In order to grant planning permission,” she explained, “a material contravention of the existing County Development Plan is required as the proposed site is not currently zoned for industrial use.”

County Manager Maurice Moloney confirmed that the council would seek a material contravention of the County Development Plan. Fitzpatrick said they were “optimistic” that the councillors would vote against the material contravention but John Ahern said that Indaver planned to apply to the EPA for a licence in April and would appeal to An Bord Pleanála if the council vote went against them. On 26 May 2003, Cork’s councillors did just that, by a 30 to 13 vote.

For two weeks the communities argued their case in the Neptune stadium at Gurranabraher in Cork, adamant that they had the high moral ground despite being told they could not air their environmental and health concerns.

The inspector calls ‘No’

In November 2003, senior inspector Phillip Jones told his board to refuse planning permission, stating that the location was wrong on topographical, geological and hydrogeological grounds. Two months later, An Bord Pleanála over-ruled their inspector, overturned the council’s decision and gave permission, citing national waste policy.

Indaver announced that this was good news for the 120 overseas pharmaceutical and chemical companies in Ireland, and their 20,000 employees.

The community alliance reacted with fury and applied to the High Court for a Judicial Review of An Bord Pleanála’s decision. Despite the court agreeing to hear the case, it was never heard.

Almost five years later, the case before the High Court was abandoned, as Indaver were required to submit a second planning application because the time limit on the first was about to expire.

• Communities submitted 20,000 objections to the establishment of a national hazardous waste incinerator

On 28 November 2008, Indaver lodged its second application with An Bord Pleanála under new regulations that allow proposed developments of “strategic importance to the state” to bypass local authority planning procedure. It wanted planning permission for the industrial burner and for a 160,000t municipal waste incinerator, plus a 15,000t waste transfer station.

The following April, with senior inspector Ms Oznur Yukel-Finn in the hot seat, An Bord Pleanála set out their rules at the Cork International Airport Hotel and heard almost 300 submissions against Indaver’s new plans for Ringaskiddy. With health issues being considered for the first time at a planning appeal board hearing, CHASE believed they knew the rules of the new game.

“In addition to submissions from the surrounding communities, submissions from the Department of the Environment, Cork County Council, Cork City Council, numerous local politicians, as well as medical, leisure, tourist and farming/food interests were received. None of these supported the proposal, and no submissions in support of the proposal were submitted by local industry.”

In January 2010, An Bord Pleanála informed Indaver that it was “considering” granting permission to build the hazardous waste incinerator but that the municipal incinerator was not appropriate “at this time, having regard to both the lay-out and limited size of the site and to the current strategy of the Cork local authorities in respect of waste management”.

In the summer of 2010, the rules of the game were changed again.

Indaver reacted first and asked Cork County Council whether various state policy updates on waste would affect the council’s waste management plan. The council said it had begun an “early review of waste management planning in the county” as a result of the updates and budgetary factors. Almost immediately, the council announced it had sold its waste collection business because of rising costs and the “highly competitive private sector marketplace”.

Despite Indaver’s confidence in Cork’s re-evaluation of its waste policy, An Bord Pleanála rejected the application, citing the risk of coastal erosion and flooding at the proposed site and incompatibility with Cork’s 2004 waste strategy. Indaver, aware that EU law and waste policy were key to the game, asked the courts to adjudicate. Indaver argued that the board had erred on both European and Irish law in making its decision, and failed to interpret government and regional policy on waste management.

Indaver maintained that the board did not have “all the facts” when it made its decision. Cork had to bring its waste strategy into line with EU and ‘national’ policy. At the 2009 hearing, that was the plan; by 2011, that plan was “no longer relevant”. The landfill diversion targets for 2013 and 2016 were under threat.

When Indaver learned that the council had abandoned its plans to build a materials recovery facility and was prepared to scrap its 2004 waste strategy, the corporate dropped the court action and announced that it would submit a third application to An Bord Pleanála. It was 19 October 2012, the day the war changed in favour of the state and industry.

Cutting to the CHASE

Ultimately, Indaver has benefitted from the state’s nonchalant attitude towards waste in the 1970s and 1980s, since Mary Harney’s Environment ministry reported that total waste solutions would be beyond the means of local authorities outside Dublin. By providing a solution to the country’s municipal waste issues, albeit one not acceptable to communities, Indaver has solved the intractable problem with hazardous waste. Ireland, regrettably for anti-incinerator campaigners, turned to alternatives too late.

• An Bord Pleanála said it was considering granting permission to build a hazardous waste incinerator

When an EPA official signs the papers granting Indaver a licence, Ireland will have its first municipal and industrial waste facility and John Ahern will have the last word.

“The waste-to-energy facility in Meath which will take in hazardous waste is the first of its kind in Ireland. It will go some way to retaining investment in Ireland such as the pharmaceutical industry and will make Ireland more attractive to foreign direct investment. Unfortunately, it will not cater for all the hazardous waste by-products that are currently exported at high cost. Ireland needs more local recovery options for waste if it is to maintain its competitiveness.”

That would make Ringaskiddy the winning move for Indaver — unless CHASE can prolong the war with a new strategy that goes beyond rhetoric, playing the game by the state’s rules and praying for miracles.

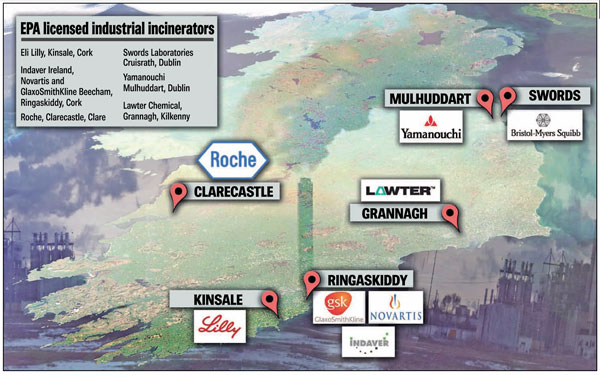

EPA licensed industrial incinerators

- Eli Lilly, Kinsale, Cork

- Indaver Ireland,

- Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline Beecham, Ringaskiddy, Cork

- Roche, Clarecastle, Clare

- Swords Laboratories Cruisrath, Dublin

- Yamanouchi, Mulhuddart, Dublin

- Lawter Chemical, Grannagh, Kilkenny