3 March 2013 Edition

Still drawing from the musical well

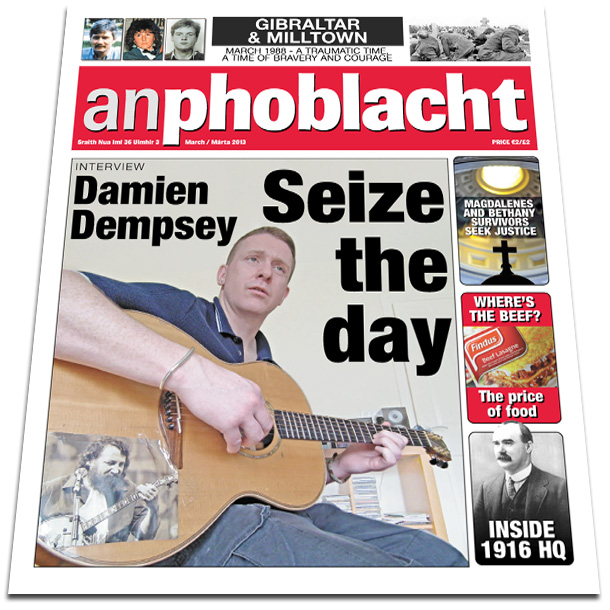

Interview: Damien Dempsey

• Damien Dempsey

‘I wanted to know why there was a war raging 90 miles away. When I was younger I had to teach myself. I learned to read between the lines’

BY THE TIME you read this, Damien Dempsey will probably be in Australia, where he starts a tour at the beginning of March. When I spoke to him in Dublin he was looking forward to singing his songs for the new wave of post-Celtic Tiger Irish emigrants.

A lot of water has flowed under the bridge since I first interviewed Damien on the Dublin northside community radio station, NEAR FM, 13 years ago. Since then, his musical journey has had a few hitches but mostly it’s been onwards and upwards, while the Celtic Tiger has long departed, leaving behind it a wrecked economy and an identity problem.

Just across the road from where we meet on a bright February afternoon stands the now internationally infamous Priory Hall apartment complex. A monument to what Damien describes as the “madness” of the Celtic Tiger era, the complex declines, abandoned and crumbling while its evacuated residents remain at the mercy of banks and Government. On his second album, Seize the Day (2003), Damien had the song Celtic Tiger:

Hear the Celtic Tiger roar

I want more

Hear the Celtic Tiger roar

I want more, more, more.

In a Hot Press interview at the time he spoke of the greed that was rampant and he predicted a collapse, with houses being repossessed. Some people didn’t like it.

“I was slagged off and jeered. ‘This fellow’s givin’ out, we’re finally doing well . We have jobs and all now.’ I could see the jobs. A lot of jobs were with multinationals, no unions, shift work, assembly lines, people had no rights, they weren’t getting trained, these multinationals could up sticks and leave any time they wanted.

“People didn’t want to hear it. It was madness. I always compare it to when the Native Americans got whiskey. They couldn’t handle it. It was like when the Irish got the money. They didn’t know how to handle it. I saw people getting SUVs and wanting holiday homes, wanting to outdo each other with bigger extensions. It was crazy. It was like crack cocaine.”

After his first album in 2000, They Don’t Teach This Shit in School, Damien’s musical career had failed to take off. His album wasn’t promoted and the airplay and gigs weren’t happening.

“People were telling me to give up the music as a career. Give up the ghost, you tried your best. My stubborness kept me going. I was around 30 when things started happening for me.”

His stubbornness did see him through — that and his deep commitment to the songs and music and their meaning.

He grew up in Donaghmede on Dublin’s northside, a working-class area, developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Many of its residents came from the north inner city. His first song at the age of 13 was about the smog that then perpetually descended on the city in winter. His home place is still reflected in his songs. Canadian Geese and Chris and Stevie, on the latest album, are very much songs of a particular place but also of universal suburban experience. Does he still get inspiration from the area?

“That’s when I write the best stuff. I’m still getting songs. There’s still a well of songs here in Donaghmede. I’m still drawing from the well. I’m still trying to write modern-day ballads. People will maybe listen in 50 years and get an idea of what it was like in these times.”

• Damien Dempsey with Mícheál Mac Donncha

Damien credits London-Irish producer John Reynolds with helping to turn his career around. This led to his second album, Seize the Day, in 2003 and he has been seizing days and nights and packed gigs and successful albums ever since. As well as common musical commitment, Damien and John have a historical connection. Damien’s great uncle, Ned Bridgeman, was in the IRA’s Four Courts garrison in 1922, and John’s great grandfather was Dan Head, killed in the IRA attack on the Four Courts in 1921 and is buried in Kilbarrack Cemetery, not far from Donaghmede.

Irish history has been a huge inspiration for Damien:

“I kind of got the impression in school that we weren’t being taught the real deal. We weren’t being taught our proper history.

“I wanted to know why there was a war raging 90 miles away. When I was younger I had to teach myself. I went to the library and read books. I learned to read between the lines.

“I got a picture of Irish history and it probably gave me strength in myself. I was a bit more proud of myself and what people went through and how they fought and struggled, persevered and survived and went abroad and dragged themselves up. Spat on and hated wherever they went. They dragged themselves up and worked very hard.

“When I went to New York I got a great sense of the Irish-Americans and how proud they were to be Irish. It helped me put my shoulders back a bit. So it was good to travel. When I saw what Irish history was, that gave me an affinity with other people around the world. It’s a great way for Irish people to get over any racism they might have against other people.

“That’s why it’s important for Irish people to know their history. I don’t know if it’s taught properly in school. The state is afraid we’ll all be republican if we are taught the proper history of Ireland. We’d probably care more about the country if we were taught its history. That gave me an affinity with other indigenous people around the world. I wanted to travel and meet them.”

To appreciate the depth of the point Damien makes here you need to be at one of his gigs when the audience joins him singing Colony, his powerful anthem that links the Irish struggle for freedom with struggles of peoples all over the world. It’s the same sentiment expressed by Bobby Sands in his poem The Rhythm of Time, which Damien has put to music and recorded.

He takes the long view. Things may be grim in Ireland but we have seen much, much worse:

“As bad as it is now in Ireland I think it’s better than it has been in a long time. If you go back into the history of the country, if you go back 100 years, it was a different story, it was a proper Third World country. Even back to the 1950s it was a nightmare. Same shit different day. With this Household Tax, years ago if you had an extra window you’ d have to pay tax on it or on a chimney or anything. These bad men haven’t gone away. The bankers have been causing wars, they’ve been doing this for centuries and centuries.”

Well, Moneyman, to you it’s all a game

You fund both sides

Then watch them kill and maim.

(Moneyman, from Almighy Love)

What does he regard as the highs in his career?

“Meeting all my heroes and singing with them. Meeting Christy Moore and singing with him. I sang with him in the Point Depot. I was that nervous that night I came out on stage and my leg was shaking. There must have been about 7,000 people there. I couldn’t stop my right leg from shaking. An auld one in the front row said: ‘Jaysus, he’s like Elvis.’ But I wasn’t trying to be like Elvis - I just couldn’t stop my leg shaking! That was a massive moment for me, to sing with one of my all-time heroes that I was listening to since I was a child. He sang a song called It’s Important, one of my songs. And then singing with Sinéad O’Connor of course, another hero of mine, a bit of a warrior woman, way ahead of her time in taking on the Church.”

Damien talks of the need for spirituality, not organised religion, but awareness of self, connection with nature, and the traditional role of the poet and bard as a provider of healing through music and critic of power. His only career ambition is to continue doing live gigs where he has a real connection with his audience, whether it’s in Vicar Street or the Sydney Opera House.

“I went through an artist’s block for a few years. It was a nightmare. The only thing I was ever good at, I thought it was gone. That got me down. That was before this album. I need to write songs that mean something to me. Songs that touch me and that’s why I keep writing them. The subject matter can be heavy but I always try and have a chink of light at the end of the song. Bob Marley and Christy Moore and Sinéad O’Connor and The Dubliners passed a positive message on to me. The music helps you through dark times in your life and in the world and I just want to pass that on.”

Before we finish he tells me he wants to do some work with the Priory Hall residents, to help their cause. As ever with Damo, the last word is positivity:

“Through the music I’ll just try and steer people towards getting into their own history, keeping a bit of spirituality, keeping a bit of hope and positivity.”

Damien Dempsey’s current album is ‘Almighty Love’. For more information on forthcoming gigs etc. see: www.damiendempsey.com