12 November 2009 Edition

Remembering the Past: The Irish Bulletin

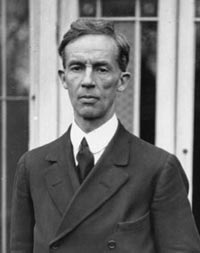

Erskine Childers

By Mícheál Mac DonnchaIN the months following the establishment of the First Dáil Éireann the British regime in Ireland continued the strict censorship of Irish newspapers that it had imposed during the European war. News within Ireland was stifled by Dublin Castle and outside Ireland the British tried to ensure that only their version of events was reported in the world’s press.

The Dáil Cabinet was conscious of the need to fight this propaganda war and to break through what Arthur Griffith had called “the paper wall” that surrounded Ireland. Even without censorship many newspapers in Ireland were hostile to Sinn Féin, while republican newspapers and publications were banned outright. In April 1919 Terence MacSwiney proposed the establishment of a daily newspaper but this did not prove practicable.

The Dáil Cabinet was conscious of the need to fight this propaganda war and to break through what Arthur Griffith had called “the paper wall” that surrounded Ireland. Even without censorship many newspapers in Ireland were hostile to Sinn Féin, while republican newspapers and publications were banned outright. In April 1919 Terence MacSwiney proposed the establishment of a daily newspaper but this did not prove practicable. By the closing months of 1919 with the struggle intensifying, there was a greater need for Ireland’s case to be heard more clearly by the wider world. On 7 November the Dáil Cabinet agreed to a scheme for a daily news bulletin to foreign correspondents, including weekly lists of atrocities committed by the British crown forces, as well as coverage of the work of the Dáil itself.

The success of the Irish Bulletin was based on the accuracy of its reports and the straightforward manner of their presentation. Rhetoric was avoided and the Irish and foreign journalists soon began to rely on the bulletin for news. It was sent out by post to hundreds of recipients in Ireland and overseas, including journalists, newspapers editors and political figures. The main journalists on the paper were Robert Brennan, Frank Gallagher and Erskine Childers.

DUBLIN CASTLE LETTERS

The Irish Bulletin was produced secretly in Dublin where it was typed up and then copied on a mimeograph machine. Its staff operated as part of the underground administration of the Dáil. It received reports from the republican network throughout the country, including IRA intelligence. It had a number of notable ‘scoops’. These included the revelation of Dublin Castle letters which showed that death threats to TDs which had been sent on Dáil notepaper in March 1920 had emanated from the Castle itself, exposing as lies the earlier British denial of involvement. Stung by the success of the Irish Bulletin the British produced a fake version of it, designed to sow confusion, but this was quickly exposed. The British also produced their own propagandist Weekly Summary, more as an attempt to boost the morale of their forces than to influence wider opinion.

Despite determined efforts by the British to close down the Irish Bulletin it operated continuously from November 1919 until the end of 1921, never missing an issue. There were many raids and ‘close shaves’. On one occasion the paper was produced in an office in Molesworth Street in the guise of an insurance company. The building was shared by a crown solicitor. The British began a raid in the area and the staff had to flee, carrying the most important papers in their pockets. The whole street was searched but the staff found later that the Bulletin office had not been touched as the British had used the building as their headquarters for the raid and thought such a respectable office was above suspicion.

Erskine Childers was appointed Director of Propaganda in February 1921 and added a new section to the Bulletin giving a weekly survey of the war, including attacks, ambushes and casualty figures. After the Treaty split Childers edited the newspaper Poblacht na hÉireann. It was because of his effectiveness in this role that the Free State hunted down and executed the former Irish Bulletin editor.

The first issue of the Irish Bulletin was published on 11 November 1919, 90 years ago his week.