24 September 2009 Edition

The rise and fall of the Stickies

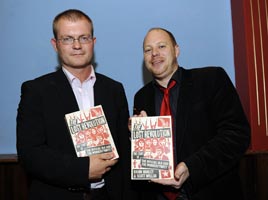

AUTHORS: Brian Hanley and Scott Millar

The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers’ Party

By Brian Hanley and Scott Millar.

Penguin Ireland.

ISBN 978-1-844-88120

Price: €21.99/£20

By Mícheál Mac Donncha

This book must rank as one of the most detailed and frank histories of any political party in Ireland or elsewhere. It tells the story of the bizarre political journey of the ‘Stickies’ from the split in the IRA and Sinn Féin in 1969 to the disintegration of the Workers’ Party and the departure of most of its leadership in 1992.

The book is primarily based on interviews with a range of members and former members of the Workers’ Party and ‘Official IRA’ and that is at once its strength and its weakness. The authors have put a huge amount of research into this and have spoken to dozens of people, giving a fascinating view from the inside of a highly secretive and conspiratorial political party. However, at key points, the absence of other perspectives is glaring. This is especially so in the coverage of the 1969 split where we get a very inadequate view of how it was seen by those on the other side of that divide.

The 1969 split was a disaster for Irish republicanism. Talented and committed leaders and activists went their separate ways and two Sinn Féins and two IRAs emerged at a time when the Orange state was collapsing and people in the 26 Counties were looking North as never before. Yet IRA Chief of Staff Cathal Goulding believed that his political project had such potential that it was worth allowing the Movement to split from top to bottom.

We need a detailed history of the build-up to the split during the ‘60s and how it happened and hopefully one will appear in due course. But even from the partial account given here, it is plain to see that Cathal Goulding and Seán Garland were set on a course that they were determined to follow, come what may. They disregarded both the widespread internal opposition to their direction and the events which were changing Northern politics fundamentally. Ironically, while the Provos were castigated as militarists, it was Goulding and Garland who used the military structure, discipline and conspiratorial tradition of the IRA to force through profound ideological changes that made a split inevitable.

When the crisis broke in the North and nationalists came under attack from the RUC and loyalists in August ‘69 the IRA was in a poor state to defend nationalist areas. The book makes clear that the IRA was still active and certainly did not “run away” but it had been allowed to deteriorate and dissatisfaction with the Dublin leadership over this issue was a key factor in the split.

More profoundly, the Goulding leadership had a flawed analysis of unionism and the flaws would become clearer as time went on. Ignoring the harsh realities of division brought about by 50 years of sectarian Unionist government, the Goulding leadership’s Northern policy was based on the belief that working-class Catholics and Protestants could be united on social and economic issues while pretending not to see the elephant in the room – the question of partition and British rule. They supported the retention of unionist majority rule at Stormont on the basis that this would lead to left/right politics in the North.

As time went on this blindness to reality developed into a political perversion so that, by the 1980s, the ‘Official IRA’ and Workers Party in the Six Counties were collaborating with the RUC, acting as informers within the nationalist community, and colluding with loyalist paramilitaries in criminal rackets. They were venomous in their opposition to the H-Block/Armagh campaign and the hunger strikers. They welcomed the use of ‘supergrasses’ by the RUC and, ironically, given Garland’s present predicament, supported political extradition. Such was their hysteria that British Labour Party conference delegates who went to hear Gerry Adams speak in 1983 were described as “ghouls” who would be “equally at home with the Yorkshire Ripper”.

The Sticks remained totally marginal in the North but in the 26 Counties they had an influence far beyond their numbers. With members in the trade union leadership and the media, the Sticks performed a very useful role for the political establishment. They provided a pseudo-left-wing critique of republicanism which complemented Government censorship of RTÉ. In the Irish Times in Dublin and the Sunday World in Belfast their journalists kept the anti-republican line while ensuring favourable coverage for the Sticks.

They were now deeply partitionist and strident in opposition to even the mildest forms of Irish nationalism. But the further they went in their denunciations of Sinn Féin and IRA ‘terrorism’ and in support of British repression, the more glaring became the contradictions in their own position. For, as this book makes clearer than ever before, the ‘Official IRA’ was still very much alive. It ran all kinds of robberies and rackets North and South to fund the Workers Party and, though it had declared a ceasefire in 1972, it had been responsible for widespread violence, not against British forces, but in feuds with the IRA and INLA, and in enforcing its presence in nationalist areas.

By the late 1980s the ‘Official IRA’ was known as ‘Group B’ and was still involved in ‘Special Activities’ to fund the party. When the RTÉ programme Today Tonight (formerly a hotbed of Sticky influence) and Magill magazine exposed much of this, ‘Group B’ resorted to threats to the journalists.

The collapse of the Soviet states caused another ideological crisis for the Sticks who had followed a strong pro-Soviet line since the mid-70s. The party was now divided between those who maintained what they saw as democratic socialism, as well as favouring the retention of ‘Group B’, and those, mainly around the party’s TDs, led by Proinsias de Rossa, who wanted to jettison ‘Group B’ and move closer to the social democratic politics of the Labour Party. (Both sides remained vehemently anti-republican). When De Rossa’s faction could not turn the party around in 1992 he split to form Democratic Left which later merged with the Labour Party and eventually took over the leadership of that party. Both the last (Pat Rabbite) and the current (Eamon Gilmore) leader of Labour are ex-Sticks.

Despite the title of the book, and notwithstanding that many of them may have been sincere revolutionaries, the Sticky project was not the revolution and the revolution is not lost. It has yet to be won and, in winning it, lessons can be learned from the rise and fall of this now defunct political force.

• This book is available from: Sinn Féin Bookshop, 58 Parnell Square, Dublin 1. Tel: (+353 1) 8148542. www.sinnfeinbookshop.com

FLAWED ANALYSIS: Cathal Goulding and Seán Garland