27 August 2010

The burning of Balbriggan

THE month of September 1920 saw an intensification of war in Ireland with the British Army, regular Royal Irish Constabulary, Black and Tans and Auxiliaries targeting the civilian population in ‘reprisals’ that had the sanction of the British Government.

THE month of September 1920 saw an intensification of war in Ireland with the British Army, regular Royal Irish Constabulary, Black and Tans and Auxiliaries targeting the civilian population in ‘reprisals’ that had the sanction of the British Government.

On September 3rd, the British regime abolished coroners’ inquests in ten Irish counties, replacing them with military inquiries. This was done to shield the crown forces from the consequences of their murderous actions. The previous March, the jury in the inquest on the murdered Sinn Féin Mayor of Cork, Tomás Mac Curtáin, laid the blame squarely at the door of the RIC and the British Cabinet. As they did later during the conflict in the Six Counties from 1969, the British responded by restricting or banning inquests altogether.

On September 8th, British ministers, after meeting an Ulster unionist delegation in London, decided to establish a force of ‘special constables’ in the Six Counties. These would become the notorious ‘B Specials’ and were set up after unionist leader James Craig urged the British Government to use the Ulster Volunteer Force for the purpose, just as it had been used as the basis for the 36th (Ulster) Division in the First World War.

Another pointer to the increasingly desperate measures being taken by the British was when the Irish Bulletin, Dáil Éireann’s official organ, exposed the use of captured Dáil notepaper by British Intelligence to send death threats to Dáil members.

A pattern had emerged where attacks by the IRA on British crown forces were followed by British reprisals in which civilians were killed and injured and buildings destroyed or looted. Many such reprisals took place around the country but the burning of the small town of Balbriggan, in north County Dublin, received worldwide attention because of its proximity to the capital, where national newspapers and foreign correspondents were based.

On September 20th 1920, in a public house in Balbriggan, two Black and Tans were shot, one of whom died. There was no evidence as to who fired the shots and one account said the shooting was the result of a quarrel. Black and Tans and Auxiliaries were based at the nearby Gormanston Camp and up to 150 of them descended on Balbriggan that night, intent on revenge.

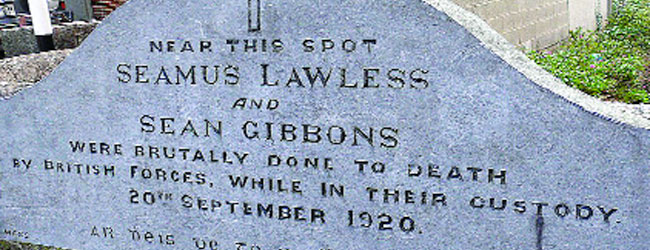

The British forces proceeded to smash windows of shops and houses in the small town. They set fire to a hosiery factory which was completely destroyed. They burned down 25 houses, forcing families to flee. Some had to take refuge in the fields. Two local young men, Séamus Lawless and Seán Gibbons, were bayoneted to death on the street by the Tans. A memorial today marks the spot where they were murdered.

Balbriggan Town Council member John Derham testified to the American Commission of Inquiry into conditions in Ireland that he had been dragged from his house by the Tans after the windows and doors were smashed. He was beaten with rifle butts and fists and he saw Lawless and Gibbons lying dead on the street.

The foreign press covered the destruction of Balbriggan, the Manchester Guardian writing:

“To realise the full horrors of that night, one has to think of bands of men inflamed with drink, raging about the streets, firing rifles wildly, burning houses here and there loudly threatening to come again tonight and complete their work.”

A British civil servant in Dublin Castle, Mark Sturgis, wrote in his diary: “Worse things can happen than the shooting up of a sink like Balbriggan.”

The British Chief Secretary for Ireland, Hamar Greenwood, was only slightly less callous in his statement to the House of Commons on October 20th when he said that from 100 to 150 men “went to Balbriggan and were determined to avenge the death of their popular comrade, shot at and murdered in cold blood. I find it is impossible out of that 150 to find the men who did the deed, who did the burning.” He went on:

“I have yet to find one authenticated case of a member of this Auxiliary Division being accused of anything but the highest conduct characteristic of them.”

In reality, the policy of ‘unofficial’ reprisals (i.e. officially carried out but officially unacknowledged as such) had sanction from the highest level. In June 1920, British Prime Minister Lloyd George had a private meeting with Hugh Tudor, top police ‘adviser’ at Dublin Castle, appointed by Winston Churchill. To Tudor, Lloyd George affirmed his full support for the reprisals policy. Tudor was appointed head of the RIC the following November.

The month before the burning of Balbriggan, Tudor had started the publication by the RIC of the Weekly Summary. This was a propaganda sheet designed not for the press and public but for the crown forces themselves, in order to boost morale and ‘psyche them up’ to carry out the terror policy.

The General Officer Com-manding the British forces in Ireland, General Sir Nevil Macready, defended the burning of Balbriggan in an interview with an Associated Press reporter. Macready said:

“But now, the machinery of the law having broken down, they [British forces] feel that there is no certain means of redress and punishment, and it is only human that they should act on their own initiative.”

In private, Macready wrote to Sir Henry Wilson that same month:

“Where reprisals have taken place, the whole atmosphere of the surrounding district has changed from one of hostility to one of cringing submission.”

In fact, British actions bred tougher resistance from the IRA and the civilian population, with the war escalating in the autumn of 1920.

Balbriggan was but the best-known of the ‘reprisal’ attacks in September 1920. There were also burnings, shootings and murders by the crown forces in Mallow, Ennistymon, Lahinch, Miltown Malbay, Tubercurry and Trim, among other places, 90 years ago this month.

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures