22 November 2007 Edition

Exploring the complexities of the Basque Country

BOOK REVIEW

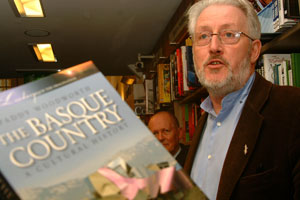

The Basque Country:

A Cultural History

By Paddy Woodworth

(Oxford University Press)

The Basque Country:

A Cultural History

By Paddy Woodworth

(Oxford University Press)

Reviewed by

Inãki Irigoein,

Basque political activist living in Dublin

PADDY Woodworth’s book is a very good introduction for those trying to make sense of the complexities of life and politics in the Basque Country.

Everybody is well aware at this stage that language is never neutral, nor is geography or history and this is the whole point of the introduction to the book because, in the Basque Country there is no such a thing as, ‘I am not interested in politics.’ In the Basque Country, every decision has its political pitfall, even when you consciously try to avoid it. As is made clear in Chapter 1, the mere concept of the Basque Country is up for discussion, depending from what side of the national debate you come from.

The book covers a massive amount of ground for such a small book – from history to culture, from tradition to the new ways of life, from architecture to nature – and it manages to give a flavour of the complexities of all the provinces that are part of the Basque Country.

I will not say that I agree with everything that is written in the book. There are some additions that would have made the book even better. But if we exclude Chapter 11, I can safely say that the criticisms that I have are very few.

Now let’s deal with Chapter 11, Don’t Mention the War: The Dark Side of Basque – and Spanish – Politics. As you can imagine, here is where the politics of the author shines through the otherwise apparently equidistant approach to the subject. The worst of all is that the chapter could have been a really good overview of the violence that is an undeniable factor in Basque politics if the author would not have peppered it with some comments that are both unhelpful and unnecessary.

What I am talking about is when the author suggests that the state’s dirty war is something in the past or when he claims that Spanish law allows all Basques to pursue their political objectives, both of these claims are manifestly untrue. Another is when the author suggests that the bomb that put an end to the last ETA ceasefire could have been planted intentionally to kill the two Ecuadoreans who died.

On the other hand, in the same chapter, he lets some things pass without much comment, like when he mentions that some of those responsible for the dirty war served very short sentences. I do not think that the crude reality of what is going on in the Spanish courts is well reflected there. The fact is that some people in prison today for acts like setting a skip on fire are serving sentences two or three times longer that what any (and there were only a few) of those involved in the dirty war have ever served. I would have liked the author to make it clear that the dirty war and torture are still realities in the Basque Country and that a Basque surname when you are in front of a judge means that your sentence doubles. Instead, the author says, “a substantial minority nurtures this sense of victimhood”. I wonder why.

Having said all that, if you are looking for a book about the Basque Country, you will be hard pressed to find something better than this.