14 December 2006 Edition

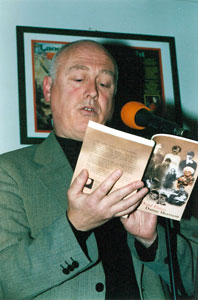

Interview - Author Danny Morrison

There’s an inner thing in every man

Author Danny Morrison is a former editor of An Phoblacht and a former Director of Publicity for Sinn Féin. He was elected to the Six County Assembly in 1982 as an abstentionist Sinn Féin member for the constituency of Mid-Ulster and missed out in the 1983 Westminster Election by 78 votes. He was also a candidate for Sinn Féin in EU elections in 1984.

Imprisoned in 1990 on charges of aiding and abetting in the detention of an RUC informer, he served eight years’ imprisonment in Long Kesh, from where he contributed articles to An Phoblacht and An Glór Gafa/ Captive Voice. He was released in 1995 and has since worked as a full-time writer. Here, he speaks to ELLA O’DWYER about his life, his republican involvement and his love of writing.

“I was born in Andersonstown [in 1953], then a 99% Catholic area. We lived in rented houses. At that time we probably wouldn’t have known who was Protestant there. I moved to the Falls in 1963 and that was a mixed area. The Cultúrlann was then a Presbyterian church and the Orangemen used to March up the Falls every twelfth of July, right up to 1964-65. There were very few Protestants living in that area so they just stopped marching there. Nobody threw a stone at them. They used to sing God Save the Queen standing on the Falls Road and nobody bothered about them.

“The first major issue for us at the time was the general election in September 1964, when Paisley threatened to march up the Falls Road and take the Tricolour out of the Sinn Féin offices in Divis Street.

“Sinn Féin was then a proscribed organisation. Billy McMillen was the candidate. The Republican Movement had just come out of the 1956-62 campaign quite demoralised, and they toyed around with different ideas, so Billy stood as a republican candidate. He was later assassinated by the INLA in a feud in 1975.

“He came last and the Unionist candidate James Killfeder won. But Paisley started a riot. He said if the RUC wouldn’t go into the offices and take the Tricolour he’d get loyalists to go in and do it.

“So the RUC came and took the Tricolour on a couple of occasions and rioting broke out. All of the public transport was disrupted. We had to walk to school, something that helped bring home to me what was going on here. Although I lived in the Falls I went to school in Andersonstown so it was a bit of a trek – about three or four miles. It was called the Divis Street riots. It was topical for us as kids and we’d heard of friends and neighbours being arrested for disorderly behaviour all because of Paisley.”

Morrison’s uncle, Harry White, was a renowned IRA figure in the 1940s.

“My uncle Harry White had been sentenced to death – charged with assassinating a Special Branch man in the South. A comrade of his had already been executed for the same charge two years previously. My uncle was later reprieved, largely because he had Seán McBride as his barrister.”

These and other factors impacted on Morrison’s decision later to become involved in the republican struggle.

“I had another uncle who was a Westminster MP. He stood as an independent republican. I didn’t hear that much about him. But I don’t think my uncles were the major reason for my joining the movement. I think it was more what I was becoming aware of through what was going on around me. Then there was the killings of John Scullion and Peter Ward – that had a big impact on me. There were big funerals for those two.” Scullion and Ward were murdered by UVF gunmen, one of whom later declared at his trial, when alluding to his motivation, that he wished he had “never heard of that man Paisley”.

“That was 1966 and the same year there was the anniversary of the 1916 Rising. But republicans were always seen to be in the minority – and by some people as an eccentric minority, because they went to jail for their beliefs when perhaps the easiest thing to do would have been to keep the heads down or emigrate or just accept the way the cards fell. There was a kind of SDLP mentality around even before that party was actually formed and republicans always opposed that mentality.”

Morrison was in his teens at this stage. He identifies three factors as having the greatest impact on his thinking: the Vietnam War, the anti-war movement that emerged from that conflict and the Civil Rights Movement.

On reflection, Morrison thinks he was ill-advised when his teachers encouraged him to pursue Maths and Physics, believing that English literature would have been a better option for him.

“I think the teachers thought nationalists needed to get into science – industry basically. I started grammar school at a time when we were climbing over barricades to go to school. Behind the barricades there was a new IRA being built.

“Myself and people from Sandy Row and the Shankill ran a pirate radio station and when the barricades went up in 1969 I handed my transmitter over to armed republicans in the Lower Falls. It was one of the transmitters used to run Radio Free Belfast. Interestingly I later realised that Radio Shankill, which was established to challenge Radio Free Belfast, was run on the transmitter belonging to my friend from the Shankill – Johnny Doke. I never saw Johnny again.”

Morrison gradually became involved in republican activity: “There was barricade duty and we all had to do our stint at that. I started doing things like selling ballot (raffle) tickets for the auxiliaries to buy arms.

“The loyalists tried to get into our area. There had been no complaints about Protestant kids trying to get to school, but then Paisley complained and said he was going to come up to our area and take the barricades down.”

Until June 1970, Morrison didn’t riot. He, as he says himself, was a bit “moralistic”. He’d approach the priests as a teenager and argue the toss. Involvement in armed struggle didn’t come very easily to him.

“I was 17 when I first rioted. When John (Lennon) and Yoko started the peace movement – ‘give peace a chance’ etc – I was taken with that.”

But events took over. During the Curfew of 1970, the IRA were looking for arms dumps, and Danny said “yes”. Asked if his parents ever knew he had created a ‘dump’ in their house, he said: “No, they never knew, although my father too was called Danny Morrison and later he was to be arrested in my name.”

Morrison’s life is marked by dual and sometimes competing agendas – his need to write and his need to address injustice. In April 1971, his sister lent him the money to buy a typewriter so that he could pursue one of those passions, but Morrison found himself using the typewriter to agitate on political matters.

“I had an idea of writing short stories, but the first thing I wrote was a letter to the Irish News highlighting the injustices that occurred in our area.”

A man he knew at the time told Danny that he would become a writer: “When I was 17 I was in the Legion of Mary. I used to go and do a night or two with homeless people in the area and the local library was a meeting place for homeless people, like this man, who was an alcoholic. He’d lost his wife and children in the Blitz. He used to drink mentholated spirits. We had great chats and he’d go to the library to read. One day he said, ‘You’ll be a writer someday.’

“I wrote down his words cryptically on a scrap of paper. At that time I used to think writers were some of those womanising alcoholics or the like,” he laughs.

After internment, it was virtually impossible for people like Morrison to focus on study. Nevertheless, he remained passionate about writing: “I was desperate to do it,” he says.

Morrison was interned in 1972 at the age of 19. He contributed articles to Republican News while interned and, on release, he was given a role that facilitated his appetite for writing: “I was asked one day if I thought I could manage being the editor of the paper. ‘Yes’, I said. I was delighted.”

In 1978, Morrison was arrested and charged with IRA membership. He represented himself in court. The republican archives of the time held copies of various items of republican interest, many of them in Morrison’s handwriting. Some of the documents were used to implicate him as an IRA Volunteer and yet there was one item that created a bit of contradiction. He had been handwriting material to be sent – telegraphed in those days – for a weekly column in the Irish People, a US-based paper aligned to the Irish republican cause. Danny spotted one item: a statement from the UVF in his own handwriting. He’d copied the UVF statement for inclusion in the Irish People. In court and representing himself, Morrison asked why, if he was being charged with IRA membership on the basis of IRA documents in his handwriting, was he not also being charged with membership of the UVF?

The judge agreed that it was a good question and he asked the same question of the prosecution. The prosecuting barrister said “Don’t be ridiculous,” at which the disgruntled judge released Danny on bail.

Morrison became Director of Publicity and finally editor of Republican News, later to be amalgamated into An Phoblacht/Republican News.

“I enjoyed almost complete authority over the paper then and I think it must be harder now to sell the paper, given that the censorship has lifted.”

Journalists, historians and political commentators frequently refer, often in negative terms, to Danny Morrison’s rhetorical question to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in 1981: “Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in this hand, and an armalite in this hand, we take power in Ireland?”

Asked about the now-famous quote, he explains: “The issue was about licensing the Ard Chomhairle to deliver on the question of Sinn Féiners standing in Assembly elections.”

At the time, and again in 1986, the tension around elections was manifest. In 1981 Morrison’s comment helped to swing the tide towards electoral participation. Although his speech reflected what many republicans were thinking at that time, Morrison is remembered as a key voice. He says he never planned the comment and that it just “came off the top of my head”.

Along with others such as Gerry Adams, Morrison was central in co-ordinating the communication (comms) travelling to and from the H-Blocks during the 1981 Hunger Strike. On his death Bobby Sands bequeathed his writings to the Republican Movement, now held by the Bobby Sands Trust, with which Morrison is involved.

Danny Morrison is now a married man with grandchildren and foresees the day when he might be a great-grandfather. Asked how difficult it was for him to forfeit the republican path in favour of his old passion, writing, he says: “The decision was made easier for me in that when I came out we were between ceasefires. Gerry (Adams) always encouraged me to write, but I think that a lot of my old comrades were disappointed. It all intensified the conflict within.”

Morrison has published a number of books – three fiction, three non-fiction and the recently-edited volume on the 1981 Hunger Strike. It was a very hard decision for Morrison to embark on a full-time writing career but, as with his former involvement in armed struggle and politics, he gives it his all. Morrison never did anything by halves and the call to write is very powerful in him.

Though he is hardly lacking in self-confidence, one of his main concerns about joining the IRA all those years ago was the fear that he might ‘break’ in the barracks under the heavy torture that was being inflicted on detainees at the time. But ‘breaking’ – for what the term is worth – was never on the cards for Morrison. In the words of Bobby Sands, there’s that ‘inner thing’ in Danny Morrison – the gift of creating ideas and turning thoughts into words. Having served two jail sentences and worked over half his life for the cause he believes in, he now feels compelled to harvest his particular gift.