1 September 2005 Edition

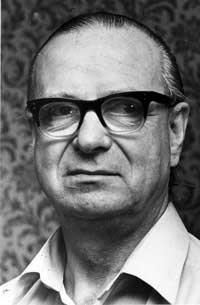

Gerry Fitt

Gerry Fitt

The differences between Irish republicans and Gerry Fitt, who died on 26 August aged 79 years were many and profound. From the days when he won the West Belfast parliamentary seat as a Republican Labour candidate, unveiled a memorial to James Connolly on the Falls Road and sustained a very public beating at the hands of the RUC, Fitt was to stride further and further east — politically and geographically — into the very heart of the state he had originally opposed.

He accepted a life peerage from Margaret Thatcher, his reward for his vocal and bitter opposition to the 1981 Hunger Strikes and deep antipathy towards the Republican Movement. Years later he stood up in the British House of Lords to speak forcefully against the proposed disbandment of the RUC, the very force which had battered him at a civil rights march in Derry on 5 October 1968.

Fitt was born in 1926 into a working-class family from the Beechmount area of Belfast, and attended the local Christian Brothers School. After a brief stint working as a barber's assistant he joined the Merchant Navy in 1941 for a 12-year period. His political career began haltingly. He stood as a Labour candidate for Belfast City Council in 1956 but lost to Paddy Devlin and had to wait a further two years before he was elected as a Labour councillor. Four years later he wrested a Stormont seat from unionism and in 1966 was elected as MP for West Belfast.

His stated intention was to use his Westminster seat to draw the attention of the British parliament to the abuses which were taking place under the unionist regime. And indeed, he achieved a degree of success in this endeavour. Fitt could not, however, persuade the then Prime Minister Harold Wilson to undertake any formal investigation — his favoured option was a Royal Commission — into wholesale denial of civil rights to the nationalist population of the Six Counties and he ultimately became deeply disillusioned with the Labour Government.

Fitt could be canny at times and understood, even in those early days, the potential power of the media. When he took part in a civil rights march in 1968, he knew that there was likely to be a confrontation with the RUC. When he was duly batoned by a police officer he lost no time in letting the world's media know about it. And it certainly had an effect. The sight of Fitt, heavily bleeding from the head was to become one of the most enduring images of the early days of the conflict. Speaking about the incident in 1988 Fitt himself said: "I knew long before that they were going to beat me up... I felt the blood running down. I thought to myself, I'm going to let that blood run because the cameras are there."

In 1970 he joined forces with John Hume and others from the Civil Rights Movement to form the SDLP, of which he became leader. Although the party was founded on a civil rights platform, by 1973 during the negotiations for the Sunningdale Agreement, Fitt's lasting disengagement with the interests and wishes of the nationalist people had become apparent. He reacted with rage, for instance, when Hume led a walk out of Stormont in protest at the horrific killings of Desmond Beattie and Séamus Cusack by the British Army. And it was clear, even to John Hume, that nationalist aspirations to unity were never going to be a priority for him.

In 1980, Fitt committed a huge political error when he agreed to take part in constitutional negotiations with the British Government without including what was referred to as an "Irish Dimension". The SDLP took a dim view, not only overturning his decision but replacing him as leader with John Hume.

But it was the Hunger Strikes in 1981 which effectively put an end to Fitt's direct involvement in politics in the Six Counties. Speaking as MP for West Belfast in the British House of Commons he begged Margaret Thatcher not to give into the demand for political status, saying:

"The government should make it clear to those engaged in the Hunger Strike that they will not obtain political status. By telling the truth, and telling it in such a way that it cannot be misunderstood, it is possible that men on Hunger Strike will realise the error of their ways and bring the strike to an end...The government must show their resolution and not allow themselves to be blackmailed by people giving support to the Hunger Strike."

The people of West Belfast could not and did not forgive him for such betrayal. In the June 1983 election he was defeated as MP by Gerry Adams. Nineteen days later he compounded his betrayal, when he became Lord Fitt of Bell's Hill at the invitation of Margaret Thatcher and moved to London, where he remained, cosseted in the luxury of the House of Lords.