26 May 2005 Edition

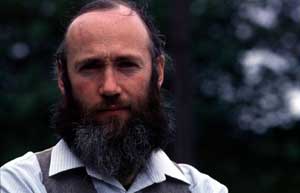

Bolger visits the twilight years

Dermot Bolger

Book Review

The Family on Paradise Pier

By Dermot Bolger

Fourth Estate

€14/£10.99

Dermot Bolger's novel is probably best described as fitting into the genre known as 'faction' — fiction based on real characters and events. As he explains in the postscript, Bolger was inspired to write the book by conversations he had with Sheila Fitzgerald, formerly Goold-Verschoyle, who is Eva, the novel's central character.

Sheila Fitzgerald was the sister of Neil Goold-Verschoyle, who, as Art in the book, is the main focus for the historical and political events described. Sheila's other brother Brian, Brendan in the novel, was arrested by the NKVD in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and died as a prisoner in the Soviet Union in 1941.

Many republicans will be familiar with Neil Goold, who was interned in the Curragh during De Valera's clampdown on republicans and left-wing dissidents during the 'Emergency'. Uinseann Mac Eoin's book, The IRA in the Twilight Years, provides useful background to Goold's time there through the reminiscences of republicans who were locked up with him.

Goold was held in Pierce Kelly's section of the camp, where he taught Russian and built a small group of pro-Soviet Marxists, some of whom later formed the Connolly Clubs and joined the Communist Party of Great Britain or the Irish Workers' League. Kelly, apparently concerned for the minds of some of those under his charge, requested that Goold be moved. That episode is crudely portrayed in the novel as a physical attack on Goold.

Goold, as Art, is not a sympathetic character. He is a naïve and unworldly figure whose youthful indignation at the plight of his poorer Donegal neighbours is transformed into a dogmatic Stalinism that blinds him to the realities of the Soviet Union. Because of that, Goold excuses the misery and terror that he has witnessed in Moscow during the 1930s and can even justify the fate of his brother at the hands of the NKVD.

Goold's naïveté leads him through a series of uncomprehending engagements with the working class, to whom he is a figure of suspicion or derision. I have no way of knowing what he was really like, but republicans who did know Goold generally had a high opinion of him, whatever their views on his politics, and he seems to have been a more complex and rounded character than the almost caricature painted by Bolger. Having said that, if Bolger's depiction is based on the account given by Goold's sister, then it must be accorded some credibility.

There are interesting vignettes of historical events and people but some of these jar. One in particular is of a big farmer named Henderson, in whose character is combined a ferocious anti-Treaty republicanism with violence to his labourers when he discovers them listening to Art's appeal to them to join the ITGWU. Such a character would have been pretty exotic among republicans in the 1930s and the suspicion must be that he is there to bolster Bolger's own anti-republican animus.

Other episodes in the book would tend to support this and that impression is not helped by a recent review by Bolger of a documentary on 'Lord Haw Haw' in which Bolger referred to IRA Volunteers writing to An Phoblacht in the 1930s looking forward to marching shoulder to shoulder with the Nazis.

Anyone familiar with the paper from the late 1920s until its suppression by Fianna Fáil in 1935 will know that such letters never appeared. An Phoblacht was unique in its anti-fascist stance and its coverage of the German opposition to the Nazis.

The main theme of the novel is the decline of the rural Protestant gentry. Eva adopts the Russian term 'byvshie liudi', or former people which Stalin applied to the displaced land owning classes in the Soviet Union, to describe their plight.

The Goolds and their neighbours, the Ffrenches, and Eva's husband's family, the Fitzgeralds of Glanmire House, are depicted as a class in decline; their culture and associations an object of scorn, disdain and bewilderment to their Catholic peasant neighbours, some of whom are prospering under the Free State and even emboldened to appear at the dinner table with the former quality.

It is easy to be sympathetic on a personal level with some of the characters who are in that predicament, particularly Eva, but is it an accurate historical portrayal of an entire class? While they may have felt uncomfortable with the trappings of a society in which Catholicism provided the main ideological basis for the new political elite, they still wielded enormous power through the banks and big commercial firms. The wealth they continued to control followed their sons and daughters to England, frustrating even the most modest attempts to develop the 26-County economy for 40 years after the Treaty.

Having said that, the historical and political aspects are only a minor quibble in what is a well written and interesting novel that does capture a sense of the time it deals with and passes the test of any work of fiction by making you engage with the characters.

BY MATT TREACY