15 July 2004 Edition

Something to be in Antrim and Newtownabbey

BY LAURA FRIEL

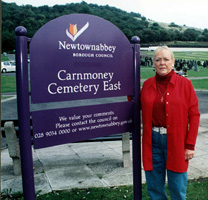

Briege Meehan at Carnmoney cemetery, where Catholic graves have been desecrated and sectarian demonstrations have been held during the annual Blessing of the Graves

Breige and Martin Meehan are heroes, not in the style of Harrison Ford's Indiana Jones or Russell Crowe's Gladiator, but in the understated manner of earlier Hollywood stars, Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mocking Bird, Henry Fonda in Twelve Angry Men and Jane Darwell in The Grapes of Wrath.

I know a word like hero can seem wholly inappropriate, over the top, when describing ordinary, everyday kind of people and when I travelled over to Ardoyne to speak to the Meehans about their role as Sinn Féin councillors, I never imagined I would be using such a term.

After all, we all know the Meehans. Martin and Breige regularly call into our offices with incidents to relate and issues to raise and to be honest, we don't give them the attention they deserve, well not quite. Another sectarian attack, another death threat; when it comes to the Meehans, well it's all pretty routine. You can see how easy it is to slip into this attitude.

But seated in their quiet, well ordered home, listening to their stories of courage and tenacity, related in a matter-of-fact, inconsequential way, the word just wouldn't stay out of my thoughts. Breige and Martin Meehan are heroes, the best kind of heroes, the bit-by-bit, day-by-day sort, whose determination to make the world a better place is as unsung as the courage it takes to do it.

Breige and Martin have been together since 1978. They collectively have five grown up children and 12 grandchildren. They have been politically active republicans their entire adult lives.

Breige was elected in 2001 as the first and so far only Sinn Féin councillor to the unionist-controlled Newtownabbey District Council. Martin was elected as a Sinn Féin councillor in Antrim District Council the same year, to a seat previously held by Pauline Davey-Kennedy. Martin McManus is the only other Sinn Féin councillor in Antrim. In last November's Assembly elections, Martin Meehan missed becoming an MLA by less than 1,000 votes.

"It is often said that unionist violence emerges when unionists feel their position as the majority is undermined," says Breige. "But our experience in both Antrim and Newtownabbey councils, both of which are overwhelmingly unionist, is completely opposite.

"Political control by unionism is accompanied by greater unionist paramilitary violence, not less. I think this is also true for other councils where nationalists are in the minority. Unionist domination has two sides, political and paramilitary. It's always been the same in the Six Counties."

The link between political and paramilitary unionism is one that even the occasional unionist acknowledges.

In April 2002, unionist councillors objected to the blessing of Catholic graves in Carnmoney cemetery. In 2001, unionist paramilitary bombers had disrupted the service. UUP councillor Ivan Hunter blamed the victims of the attack and called for the service to be banned on the grounds that it "caused great upset to many people and created a civic disturbance".

An independent socialist councillor, Mark Langhammer, noted that the uproar in the unionist controlled council over Cemetery Sunday "created a context where it was possible to burn down churches in this borough".

And burning Catholic churches is something unionist paramilitaries in Newtownabbey do frequently. A recent study by the Community Relations Council reported "a period of coordinated attacks on places of worship and religious sites in Newtownabbey" from June 2001 to September 2003.

The report, compiled by an independent consultancy firm and headed by Fee Ching Leong, also noted that in some cases those who had carried out the attacks had been "fired up by politicians in the borough". Of the 23 documented incidents, 19 sectarian attacks had been carried out against Catholic churches, premises and services.

The attacks included the destruction of St Bernard's Catholic Church; arson attacks on St Mary's on the Hill, the desecration of Catholic graves and rioting by a unionist mob during a Catholic service. The report noted: "It is evident that most of the attacks/incidents were orchestrated by loyalists." The report describes sectarianism in Newtownabbey as "raw, real and ongoing".

"In the past, unionist paramilitary violence has been explained away as a response to the IRA's campaign," says Martin, "but curiously, the level and frequency of unionist threats and violence against Briege and I, and the rest of our family, has dramatically increased since the IRA cessation, when we embraced the peace process."

It's an observation reiterated by the CRC report. "During the post-ceasefire period and particularly since the Agreement in 1998, there has been a significant increase in sectarian activity," writes Fee Ching Leong.

The report recommends inclusive dialogue. "The all-encompassing recommendation is for government, politicians, paramilitaries, the churches and the general community to engage in dialogue." The author suggests that such dialogue should be structured "following specific forms of conflict resolution",

But both Breige and Martin have found, with the exception of hurling abuse, that unionist councillors refuse to engage in any kind of dialogue. Indeed, almost without exception, they won't even speak or acknowledge their nationalist political colleagues.

"At first it was all abuse, a sort of public ritual humiliation within the council chambers. Sometimes I would arrive home shaking and tearful but I wouldn't let it silence or stop me," says Breige.

"The rest of the time I'm ignored, no one will speak or acknowledge me. They are trying to freeze me out, but I won't let it work. At first, after the abuse I received in the council chambers, I think they all thought I would scurry home straight away, but I didn't. I went to the members' tea room.

"When the other councillors, saw me sitting there, they left, one by one. I just sat there on my own. It went on like this for weeks, until, well I guess they started to think, just who is putting who out and they drifted back in. Now we all take our tea in the tea room; no one speaks to me but I've had the occasional cup of tea passed to me. I guess that has to be progress."

And life in Newtownabbey Council isn't without its humorous side. Breige recalls a visiting Presbyterian minister who refused to shake her by the hand only moments after delivering a "Love thy neighbour" address during council prayers. "Don't come near me," were his actual words. "Your hands are covered in blood."

The CRC report notes former Newtownabbey PSNI chief Brendan McGuigan's report of October 2002. "The 17 ongoing murder investigations in Newtownabbey contribute to illustrating the scale of overt sectarianism in the borough." He was reported to have said that "a large percentage of the killings had been carried out by loyalist paramilitaries".

Recent killings by unionist paramilitaries include that of Daniel McColgan, a Catholic postman shot dead in Rathcoole; Gavin Brett, shot dead as he chatted with his Catholic friends; Trevor Lowry, kicked to death in the mistaken belief he was a Catholic; Gary Moore, a Catholic building worker shot dead in Monkstown; and Gerard Lawlor, a Catholic teenager shot dead on the outskirts of Newtownabbey.

When Martin was first elected as a councillor, Antrim council was like "a Protestant council for a Protestant people", says Martin, borrowing Carson's now infamous comment. "The few SDLP councillors elected to the borough payed lip service to challenging discrimination but did nothing," he says.

"When it comes to sectarianism there's a kind of collective amnesia in Antrim Council," says Martin. "In recent years there have been over 200 Catholic families intimidated out of their homes but such matters are almost universally ignored.

"I've repeatedly called for the establishment of a community forum to begin to tackle sectarianism but unionist councillors won't participate. They'd rather deny it's happening than face up to it."

Inside the Meehans' home, as we sip coffee and chat amongst the plants and family photographs of a typical domestic scene, it's hard to appreciate the constant threat of unionist paramilitary violence which participation in unionist controlled district councils has brought into the Meehans' lives.

"Six months ago, the PSNI arrived during a council meeting and informed me that there was an imminent and viable threat to my life," says Martin. "They wanted to escort me from the building. But what would be the point of that? I said I was returning to the chamber and continuing with my work. I didn't want escorting anywhere. I belonged where I was."

The threats against the Meehans are so numerous that they have asked the

PSNI not to wake them with any warnings during the night. "We told them to

pin the warning on the door and we'd deal with it in the morning," says

Martin, "otherwise we would hardly get a night's sleep." And somehow John

Lennon's words started to ring in my head, "a working class hero is

something to be".

The threats against the Meehans are so numerous that they have asked the

PSNI not to wake them with any warnings during the night. "We told them to

pin the warning on the door and we'd deal with it in the morning," says

Martin, "otherwise we would hardly get a night's sleep." And somehow John

Lennon's words started to ring in my head, "a working class hero is

something to be".