1 April 2004 Edition

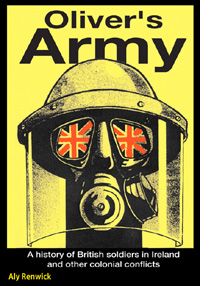

Oliver's Army

BY FERN LANE

This John Bull is now a mighty chap, boys

At the world his fingers he can snap, boys

Eastward - Westward - you may turn your head

There you'll see the giant trail of red

Dyed with the blood of England's bravest sons

Bought with their lives - now guarded by her guns

Red is the colour of our Empire laid

England will see the tint shall never fade

Full of pluck he's brimming full

Is young John Bull

And he's happy when we let him have his head

It's a feather in his cap

When he's helped to paint the map

With another little patch of red.

From Another Little Patch of Red, Victorian music hall song

Some 45 years ago, as a 15-year-old boy from the lowlands of Scotland, Aly Renwick was seduced by the British Army's recruiting campaign, a siren call which promised young men of his generation the scarce opportunity to learn a trade and travel the world.

Only after he had signed up and committed himself to more than a decade's service did the reality of life in the British Army become apparent. His subsequent experience, both of the structures of the army itself and of the way in which it operated in the British colonies in the dying days of empire, convinced him that the army, and indeed the British state, could never be a force for good where it occupied another country. Renwick spent much of the next eight years attempting to get out of the army before, increasingly alarmed by his open radicalism, his superiors finally decided to allow him to buy himself out.

After leaving and having been thoroughly politicised in the process, Renwick threw himself into activism, joining various solidarity and anti-war movements, along the way becoming more and more interested in the British state's role in Ireland and the colonial war then raging in the Six Counties. In 1974, as the British Army continued to indulge itself in the sort of behaviour against the civilian population which he recognised only too well, he became a founder member of the Troops Out Movement.

As a former soldier, he brought to the question of the British presence in Ireland a very particular and rather unusual perspective. He was also deeply aware of the psychological damage which the British Army inflicted on an alarming number of its own men, a phenomenon he went on to document in his book Hidden Wounds. In it, he exposed the disproportionate number of former British soldiers, particularly those who served in the North of Ireland, who afterwards experienced severe mental health problems and in many cases ended up in prison after committing crimes of extreme violence.

30th anniversary

Now, to mark the 30th anniversary of the Troops Out Movement, Renwick has brought together four decades of experience and study in his new work, Oliver's Army, a comprehensive history of the British Army in the multitude of colonial conflicts since Elizabeth I's Irish wars in the 16th Century. The work also examines in detail the economic imperative that drove colonialism, the unbridled desire to make money which led directly to Britain's involvement in the slave trade, in drugs trafficking and in the plunder of the world's natural resources to facilitate the industrial revolution at home.

Renwick was partly motivated to produce the book, he says, by the fact that, because of its natural antagonism to the military, the British left had historically paid scant attention to the function or character of the British Army, even though the military machine was an essential part of the British empire. He was also intrigued by British soldiers throughout history who, like himself, had developed political views that put them at odds with their employers. One example he uses is the Levellers, a number of whom defied Oliver Cromwell's order to wage war on the Irish and "tame such wild beasts". They paid with their lives for their refusal to participate in the massacres carried out by the Lord Protector's army.

Class structure

It was, however, not Ireland that first provoked Renwick's deep aversion to Britain's imperial project. Although from Scottish Presbyterian stock, and from an area of the country steeped in the history of the Covenanters — the ultra-Protestant 17th Century movement which challenged the British monarchy's claim to rule by divine right and its position as head of the established church, thus putting it into direct confrontation with the doomed Charles I — his own family were relaxed about their faith and he grew up unaware of the anti-Catholic sectarianism that existed, still exists, in Scotland. A lifelong Rangers supporter, he would go to Old Firm matches and be mystified at the songs and chants coming from those around him. He was equally unaware, as were most people in Britain, of the abuses being perpetrated a few miles away across the Irish sea or indeed elsewhere in the world. On joining the army, however, the first lesson he learned was about class rather than race.

"I wasn't really political at all when I went into the army" he explains, "but at the apprentice school we had the last of the national servicemen who were in the Education Corps and who were very anti-army. At first I thought this was wrong, but then I learned a bit more and realised they were right. The class structure is very, very clear in the army. It's a bit like the feudal system actually".

His anti-imperialism came into being when he was sent to Thailand as the Vietnam War raged nearby. "I could see the poverty there, I could see the repression" he says. "Around us was a local Thai militia guarding us and they used to go around with cowboy hats and pump-action shotguns and they treated local people terribly. At a nearby American airbase, where we went at weekends, it was like one big brothel. You could see the corruption the West was bringing into the country. There was a Thai insurgency going on at the time, I thought, yeah, they're quite right to do it."

Institutionalised racism

He also received his first lesson in how the British Army conditions its men to regard indigenous peoples. "When you go to these places, the army tells you to have nothing to do with the locals. As soon as we got to our isolated camp, this CO gave us a lecture and told us 'the regiment which was here before you called the locals Noggies but I don't want to catch any of you calling them that'. Of course, the next day everybody was calling the people Noggies. He meant to do that, but was distancing himself from it. It ensured that you had a particular attitude towards the locals and treated them as a lesser form of human being. That tended to happen everywhere".

In Kenya, Renwick also found himself identifying with the plight of the people. Although instructed not to, he would go to the nearest village and engage with the community. Less than a decade before, the British Army had been involved in what he believes is one of its most savage colonial campaigns, the war against the Mau Mau, during the course of which it slaughtered thousands of people, including civilians, unrestrained by public opinion at home or international condemnation. Some recent historians have suggested that as many as 30,000 Mau Mau fighters were killed and 80,000 imprisoned during the course of the conflict. Despite this, Renwick was treated well by the Kenyans and, as a result, promised himself that he would one day "find out what happened there and tell people about it". Sure enough, he devotes a chapter of Oliver's Army to the war in Kenya.

Colonialism in Ireland

In 1968 he found himself in the North of Ireland and realised that, even though the conflict was yet to fully erupt, here was just another example of British colonialism at work. It is these similarities and the pattern of British colonial strategy throughout history that underpins his new work. Oliver's Army opens with a scenario which could have been played out throughout South Armagh during the 1980s and early 1990s, but which in fact refers back 400 years to the reign of Elizabeth I.

"In the North of Ireland, English soldiers scanned the alien landscape surrounding their forts. Out into that hostile territory, officers regularly dispatched patrols, to seek out their invisible enemy. The soldiers were often hard-pressed, usually fed up and longed for the day they could go home. Back in London, the better-off grumbled about pollution, street crime, the homeless poor and the cost of the war in Ireland."

Crushing popular resistance

When the British Army was sent onto the streets of Belfast and Derry, Renwick understood the implications immediately. It was being used as the military had always been used — to crush popular resistance to British rule. Bloody Sunday, and in particular the use of the Paras, was, Renwick believes, part of a well-practiced strategy for dealing with popular uprisings.

"Whenever I met up with any of the infantry regiments" he says, "I always thought, Christ, how brainwashed these people are; it was very difficult to speak to them or have any sensible discussion. The worst of these regiments was the Paras.

"If you look at the counter-insurgency strategy of the British, and this goes back to the United Irishmen, one of the things they always do is try to draw the radical element into a premature insurgency. Then they can throw in their superior forces and try to smash it before it has properly started."

This tactic, he adds, also allows the state to level the charge of 'terrorism' at the resistance and its leadership and provides the necessary political cover it needs to introduce political and military repression in the hope of suffocating independence movements at birth.

"They did that against the United Irishmen and they did it in the colonial wars," says Renwick. "There is a theory about Bloody Sunday that the Paras were trying draw the IRA into a firefight on the day. That may well have been part of it, but I think it was part of a wider strategy to provoke the IRA into premature action. The Paras had also carried out a number of other operations at that time, and I am sure that is what they were trying to do."

Propaganda war

In all of Britain's colonial exploits, the propaganda war was as important as the military campaign. Leaders of resistance movements were invariably individually and systematically demonised, whilst their supporters were labelled, amongst other things, as criminals and psychopaths.

However, Renwick acutely observes that when the British state has, in its own interests, decided to negotiate with those they have previously denounced as terrorists, it has created another set of problems.

"In wars, the politicians can switch easily" he says. "For example, in Kenya the leader of the Mau Mau, Jomo Kenyatta, was referred to by the British as 'the leader of Darkness' and 'the greatest terrorist there has ever been'."

But, when the British Government realised that its attempts to impose a puppet government on the Kenyan people was not going to work, they finally turned to Kenyatta to facilitate their exit strategy from the country.

"Suddenly, this 'terrorist' was in Downing Street negotiating with the government. The politicians can change just like that, because for them it's just about gaining an advantage. But the soldiers and security forces really do believe the propaganda and they can't just switch." This inability by those who have been are the forefront of imposing British rule to adapt to the new political realities means that the propaganda war, and indeed covert military action, can continue on long after the conflict should have come to an end.

Renwick's observation was perfectly illustrated less than a week after our interview, when a bewildered British public was treated to the sight of their prime minister shaking the hand of Colonel Gadafy. Quite unexpectedly, a man they had been repeatedly and forcibly told by successive British Governments was little short of a devil, an irredeemable tyrant, a madman, friend of 'terrorists' throughout the world, was Tony Blair's new best friend and a thoroughly decent chap.

For the government, of course, it was primarily a matter of economic expediency — the 'advantage' to which Renwick refers — but so deeply is the British propaganda machine's portrayal of Gadafy as a crazed dictator embedded in the British psyche that the sight of Tony Blair being welcomed into his tent caused profound confusion and shock throughout the country.

Crucible of colonial policy

The North of Ireland and the history of the British Army's involvement in Ireland is, Renwick contends, rather more complex than that. For that reason, half of Oliver's Army is dedicated to Ireland. It was, after all, Britain's first colony and the crucible in which Britain's colonial strategy was forged. Renwick believes that a significant element of the British political establishment, including within the security services, still harbours the fantasy of victory over republicans, and so has not come to terms with a British Government negotiating with those who were loudly denounced as terrorists for over 30 years.

"The British couldn't defeat the IRA but there are still some politicians who would like to find a way of doing that," he says. As a result, "there is quite a lot of political backing for the reactionaries in the army and intelligence services".

Further, he argues, this reactionary element in British politics has its roots as far back as partition. "If you look at the partition of Ireland, that was started by British unionists, not just Irish unionists in the North of Ireland. They got Carson to front it and then it built up amongst people in the North, the industrialists and landowners, who gradually brought along the working class with them to oppose home rule.

"I think British unionism is still very strong and it exists in every party. The British might not have much of an empire, but these people still think they are top dogs. They want Ireland resolved their way."

He thinks that, even now, this unionist element is working to undermine the Peace Process. "The conflict might have stopped — except for the violence by loyalist groups — but the propaganda war is still going very strong and part of that is a re-writing of history about what the British were doing there. That means presenting it as the two-tribes story.

"These people really don't want a view to go around that the people they fought for 30 years have got what they wanted, and I think they will go to some lengths to stop that happening".

• Oliver's Army is available to read or download at one chapter per month on the Troops Out web site at www.troopsoutmovement.com. Chapters are posted on the 15th of each month.