22 January 2004 Edition

Ten years after Section 31

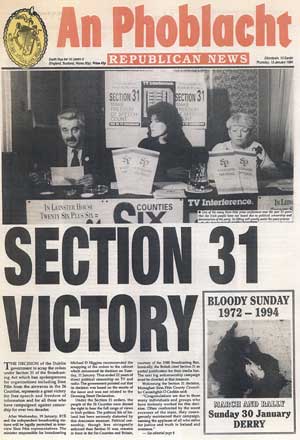

Ten years ago this week, the odious Section 31 censorship restrictions in the 26 Counties were finally lifted. From midnight on Wednesday 19 January 1994, radio and TV reporters in the South were legally permitted to interview Sinn Féin representatives. Michael D Higins had announced a cabinet decision to scrap the offending orders on Tuesday 11 January, ending 22 years of direct political censorship. The legislation was not repealed, however, and the undemocratic power to censor by Ministerial order remains in situ to this day.

In April 1993, then Sinn Féin member and trade union leader Larry O'Toole had seen the Supreme Court put a second nail in the coffin of Section 31. The first nail had been driven home the previous July, when the High Court found that RTÉ had illegally banned Larry O'Toole from the airwaves under Section 31 of the Broadcasting Act.

Larry represented fellow union members in the Gateaux bakery dispute in Finglas in Dublin in 1990. RTÉ broadcast an interview with him as the workers' leader. RTÉ interviewed him again, but then refused to broadcast Larry's views. RTÉ confirmed it was because he was a member of Sinn Féin. The Section 31 censorship law banned spokespersons for Sinn Féin. RTÉ extended it to ban all members, no matter what they were talking about or whether they were speaking on behalf of Sinn Féin or not.

Censorship

Section 31 was brought in by Fianna Fáil in 1971 to deny a voice to republicans and to deny the population of the 26 Counties the truth about British brutality in the North. The conservative elite that ruled the South wanted to talk about unity but not do anything about it. They panicked when nationalists in the North rose up against the British Army and unionist reaction. A system of thought control was instituted by Jack Lynch and reinforced by the Cosgrave/Cooney/O'Brien government after 1973.

RTÉ independence was squashed. The Authority was sacked, independent reporters lost their jobs or were moved to non-controversial areas like religion and children's programmes. RTÉ management brought in a regime of self-censorship that suppressed investigations into the Dublin-Monaghan bombings, the Garda Heavy Gang and the Birmingham Six. The NUJ said in 1976 that journalists were afraid to question government policy on the North.

Self-censorship

Openly anti-republican journalists were promoted and independent journalists suffered McCarthy type smears. Now President Mary McAleese recounts how she was ridiculed in RTÉ when she said that Bobby Sands could win the 1981 Fermanagh/South Tyrone By-election. According to McAleese, RTÉ's Joe Mulholland passively presided over a team that called RTÉ's Forbes McFaul "a fucking Provo" because they did not like a report on the Hunger Strikes.

This was typical of the atmosphere of suffocating anti-republicanism and anti-objectivity that thrived in RTÉ. Some RTÉ journalists openly campaigned to retain censorship. They were in tune with their managerial and political masters. They now write for the Sunday Independent, still batting on the same sticky wicket.

Joe Mulholland

It was fitting, therefore, that it was Joe Mulholland who wrote to Larry O'Toole in late 1990, confirming that he was banned under Section 31. These were the letters that the High Court confirmed as an illegal extension of censorship. The RTE news manager who claimed to be upholding the law and to be opposing republican lawbreaking was found to be a lawbreaker on behalf of RTÉ and a willing self-censor.

I'm RTÉ - censor me!

After the High Court judgement, RTÉ was freed to interview Sinn Féin members involved in trade union, community or other activities. What did RTÉ do? Did they welcome this increase in their editorial freedom? No, they refused to obey the judgement and appealed to the Supreme Court to be recensored. This decision bounced through increasingly astonished editorial rooms around the world. The reaction of the prestigious US Newspaper Guild was typical:

"We are astonished that RTÉ, instead of welcoming this liberal interpretation of an abhorrent censorship statute, is asking the Irish Supreme Court for a greater restriction of its free-speech rights."

Supreme Court

When the appeal was heard, even the conservative Supreme Court was astonished. When asked by the Court, RTÉ said that they would refuse to allow an actor who was a member of Sinn Féin to appear in a soap ad. The decision of the Court was clear: RTÉ had gone far beyond the law. RTÉ's confident regime of lies, half-truths and promotion of anti-republican propaganda was exposed. The eyes of the audience were opened to the sorry excuse for journalism to which RTÉ had been reduced.

Larry O'Toole and Sinn Féin went on to greater success. Larry, who had paved the way for the free debate that allowed the peace process to blossom, is now a councillor in Dublin. Sinn Féin used the case to begin to break the wall of silence in the South. The audience already suspected that something was wrong when Bobby Sands and other republicans were elected in the North. The winning of the Larry O'Toole case strengthened the hand of then Minister Michael D Higgins when he got rid of Section 31 altogether in January 1994, a full eight months before the IRA cessation in August.

RTÉ was dragged kicking and screaming into a regime of non-censorship ten years ago this month.